When you live in the country but you’d like to know how others see the country then you need to head for the city. That’s what we did last week to indulge in a double dose of artistic genius served up for our consumption at Tate Britain.

Arrived at Millbank by boat on one of the catamaran Uber river taxies that ply their trade on the Thames. Pricey, but worth it for the vistas afforded. Powerful engines allow for nimble sideways docking and a surprising turn of speed on the fast flowing floodwaters. Graceful bridges backed by sky blocking glass walled monoliths at Vauxhall with remnants of more graceful human scale buildings elsewhere on the river banks.

JMW Turner and John Constable. The two mighty creative engines that powered and defined the art of landscape painting in early C19th England. The Tate exhibition bills the two men as ‘Rivals and Originals’ and an intriguing combo they proved to be when viewed here in tandem.

Weaving in and out of the mass of fellow visitors we were skilfully drawn into their overlapping visions of a land and people in flux, complimenting and contradictory by turns.

Both men were out touring in summer and working up drawings and sketches to a finished state back in their respective London studios throughout the winter, for display at the Royal Academy show, where they’d eventually secure top billing as leading members; feted, criticized and praised in equal measure by critics, patrons and public alike.

We were introduced to two very different personalities from contrasting social backgrounds. Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851) was the son of a Devon born barber and wigmaker who had set up shop in Covent Garden. The proud father displayed his precocious 15 year old son’s drawings in the shop window to attract custom.

By contrast Constable’s father was a prosperous miller and coal merchant in rural Suffolk who disapproved of his son’s artistic ambitions. John Constable (1776-1837) comes across as an introspective, conservative and conscientious countryman while Turner was quite at home in the capital; an eccentric showman and gallery owner, secure in his own genius.

Against both their families initial opposition Constable married Maria Bicknell, a neighbour and childhood sweetheart, and subsequently supported a large family of seven children. For a while they lived out of London, in Hampstead village and Brighton, for the sake of Maria’s fragile health. Success came much later to him than it did Turner. Scaling up to work on larger canvasses his ‘Six footers’ helped secure artistic and economic success on being accepted as a member of the R.A. in 1829. Turner never married, though it’s believed he fathered two illegitimate daughters who he looked after. He also had Sandycombe lodge built in Twickenham for his widowed father. A fascinating miniature Italianate villa, still standing, recently restored and well worth a visit.

The exhibition displays a combined 170 works by the two artists. Constable’s masterpieces with the greatest appeal show us the working people of his native Suffolk going about their business in a quintessentially English pastoral setting. It seems idyllic on the surface but was often the opposite due to the huge changes wrought by the agricultural revolution then in full swing. A situation chronicled by contemporaries like William Cobbett in his ‘Rural Rides’ series of newspaper reports across the southern English counties.

I like this Constable picture of a muck heap, painted as a childhood friend’s wedding gift. Not the most obvious subject for a conjugal gift…Or is it? Composted fertility, spread on the land to increase yields, has a more obvious meaning. Like his most famous painting ‘The Haywain’ collie and patches of red feature as signatures to this otherwise everyday rural scene.

In Turner’s thrilling immersion we’re pitched into the dynamics of mechanised invention engaged with great elemental forces . ‘Snow storm – Steamboat off a Harbour’s Mouth’ (1842) is an outstanding example of the artist’s innovative style. Turner claimed he was lashed to a mast so he could safely observe the scene. I mused to think how much more disorientating this kind of artistic vision would have been when first viewed by the public.

By way of contrast Constable reveres the age old crafts – boat building in a dry dock off the River Stour. Barges like this floated his father’s stores of grain to Flatford mill and beyond. They were the foundations of the family’s fortunes and are lovingly captured in this oil painting of 1815. Constable must have revisited his childhood self in such scenes. A warm memory, in his own words, of a ‘careless boyhood…which made me a painter.’

Constable’s studies of Salisbury Cathedral in different weathers are famous works, reminding us of his deep Anglican faith and concern for the church in the face of social and religious reform. I loved the attention to detail in this painting, commissioned by the bishop, seen at the far left of the picture with his wife. Constable’s celebrated portrayal of clouds and loose handling of paint would prove a major influence on contemporary French artists, helping to lay the foundations of impressionism. That would not have impressed his patron though, who we are told, disliked the conflicted cumulous and wanted a more serene sky.

My eye was more drawn down earthwards, to the creatures in the foreground. Like the work of the C17th Dutch master Aelbert Cuyp, Constable clearly had a soft spot for cows, and they seem to represent the kind of rural contentment and prosperity he so valued. The beast on the left, having just drunk from the river, drools water while on the right a house martin hovers to catch flies over the stream.

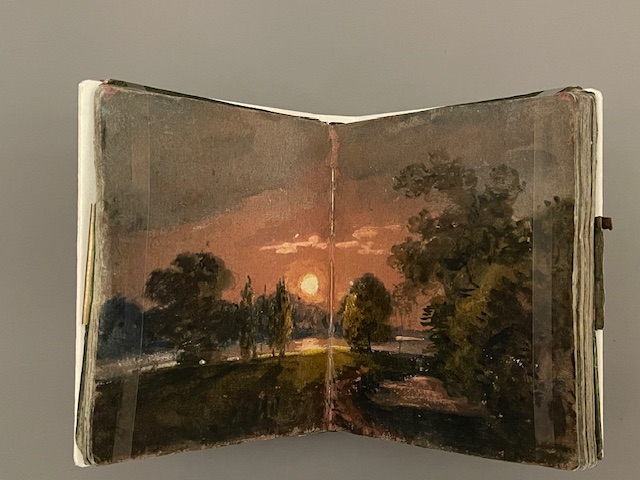

Turner travelled extensively all over Britain and ,during breaks in the Napoleonic wars, across western Europe too. He worked rapid sketches in different mediums. I liked this small notebook sunset from a tour of 1796-7 executed in gouache, pencil & watercolour.

Constable too was no slouch on this outdoor tour mission. Six weeks spent touring the Lake District in 1806 sharpened his drawing skills as this fine pencil sketch of Borrowdale shows…I wondered if he ever met the Wordsworth’s on his perambulations then? What a conversation the Cumbrian poet and his sister may have had with artist from East Anglia.

Turner’s association with Northumberland is reflected in a handful of paintings on show. ‘Keelmen Heaving in Coals by Moonlight’ is one. It’s not specified which Tyne river port of Shields – North or South – is referred to. The image is typically dramatic yet also has a melancholic tone. The keelmen transferred vast amounts of regionally mined coal from their barges (keels) to sail boats bound for London and other rapidly expanding industrial towns and cities. But It’s 1835 and the rapid spread of railways is already making transport by these means redundant.

At the other end of the county Turner was drawn both as a young artist of 22 and as an old master to the ruins of Norham Castle on the English bank of the River Tweed, the boundary with Scotland. He clearly loved the place and his views at sunrise were recalibrated from the infused romance of 1823 (above) to light drenched abstraction in 1845 (below). The latter interpretation opened the door to modernism and, by acknowledgement, the major contemporary art prize awarded in his name.

All in all a great show which does both artists justice in refreshing our understanding, documenting and illuminating their roles in that revolutionary age. The exhibition continues to 12th April. https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/turner-and-constable

On leaving we emerged into a street lined with mature plane trees, their bare branch stumps rounded like boxing gloves, punching the grey London sky. After hours infused in great art you can’t help but wonder at these natural forms tailored to urban life, like an outside extension to the gallery…Wonder what JMW and John would have made of them?