Fifty years ago I was living and working on Teesside as an actor and drama workshops organiser for the Billingham Forum’s Young People’s Theatre Co. We enjoyed free outdoor events marking the 150th anniversary of the opening of the world’s first public passenger steam railway train between Stockton and Darlington. A souvenir from that time is this little China mug, now sadly minus its handle, but otherwise intact and very pretty.

The long train of 1st, 2nd and 3rd class passengers, preceded by a rider on horseback for safety reasons, set off from Shildon in Co. Durham on the 27th September 1825 travelling the 21.5 miles to Stockton, via Darlington, at an average speed of 9mph, cheered on by crowds of excited onlookers.

Skerne Bridge, seen in the painting above, is still there today, part of the Hopetown site. The oldest railway bridge in the world still carrying a working rail route.

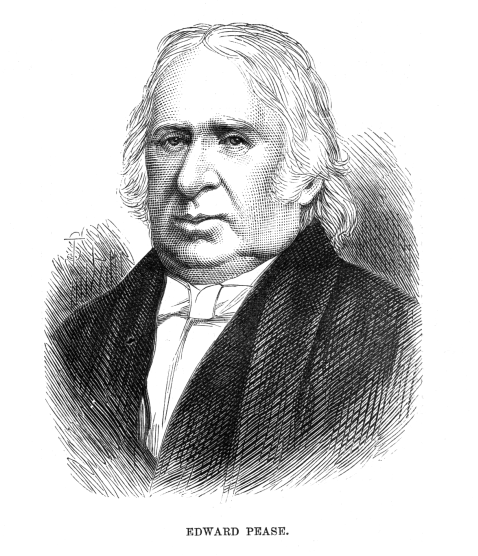

George Stephenson and his son Robert were the Tyneside engineers who gave us ‘Locomotion’, the engine that pulled those carriages on that triumphant day. Edward Pease, a leading Darlington Quaker (member of the Religious Society of Friends), was a retired wool merchant who had the time and capital to head the consortium of local businessmen were behind the scheme. The original plan was for a horse drawn tramway to transport coal from the mines in the Durham hills to the estuary port of Stockton-on-Tees where it could be shipped to the rest of the country. Stephenson Snr. persuaded the money men to opt for his newly invented coal fired steam engine instead. Adding passengers to commercial goods and loads of coal was something of an afterthought, but would have the greatest of consequences.

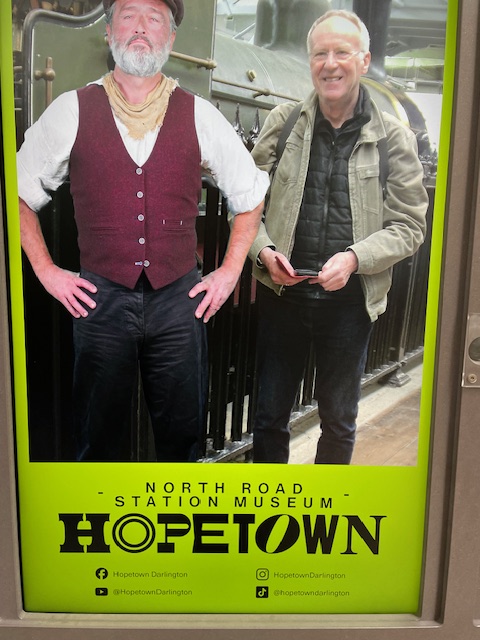

All this and much more my friend Rob and I learnt when we visited Hopetown in Darlington last week, in the year that sees the 200th anniversary of the Stockton & Darlington. Formerly known as ‘The Head of Steam’ museum at North Road railway station, the 7.5 acre heritage site has been transformed with a multi-million pound investment programme to make it a major regional tourist attraction and educational resource. Entry is free (donations welcomed) and the amount of digitalised interactive displays shows the ethos is about engaging with families and school parties to tell a spirited, many layered story. Exterior soft play areas and an adventure playground are other family attractions that help justify the public investment and draw the crowds.

We didn’t quite know what to expect but quickly became engrossed with what was on offer. The interactive stuff – being addressed by station master and engine driver holograms for instance and having our photos taken with them – sparked fun and laughter. Think the planners have got the mix of serious study material and simpler, bold displays about right, opening vistas for the curious and engaging visitors in the interplay of man and machinery.

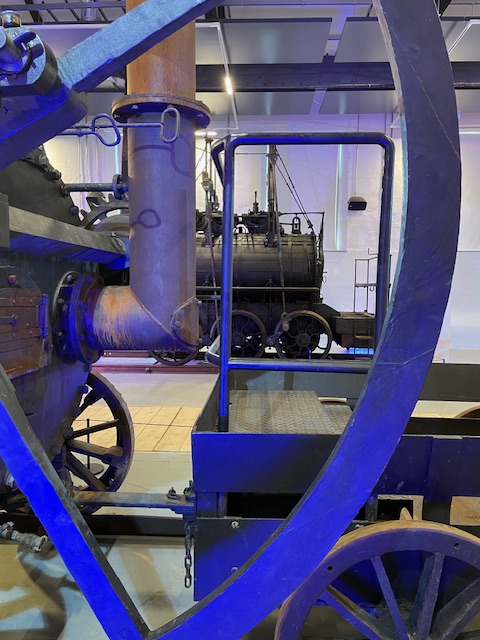

The Hopetown site, roughly triangular in size, consists of the original engine shed (1833) now the shop and café (above); station hall and offices (1842) now an exhibition area with locos and carriages, the Carriage Works (1853) with its huge open archive and large exhibition hall with awesome replicas of early engines, part of the ‘Railway Pioneers’ exhibition currently showing.

Completing the building line up is the new, purpose built Darlington Locomotive Works where 21st century steam locos are being made by a charitable trust and volunteers, the workshops overseen from a tower housing public viewing gallery.

Highlights? I think anyone who visits a heritage site is invariably fascinated by the unchanging necessities of everyday living and how each generation deals with them. That’s why the original station toilets were fascinating. Cast iron urinals, tiled walls and cubicles. Throw in the reputed ghost of a porter who committed suicide here in the 1840s that is believed to still haunt the place and you’ve got it made.

The simple elegant design of the original early Victorian station (above) entrance and its extension reflect the world view of those local Quaker company directors. The exuberant emerging Gothic style was not for them.

Britain being Britain the three original carriages on display remind us of rigid social and economic classification. First class enjoys padded seating and privacy while third class (above) is an array of hard benches and a hole in the roof to let out smoke and/or let in light. Second class a mix of both.

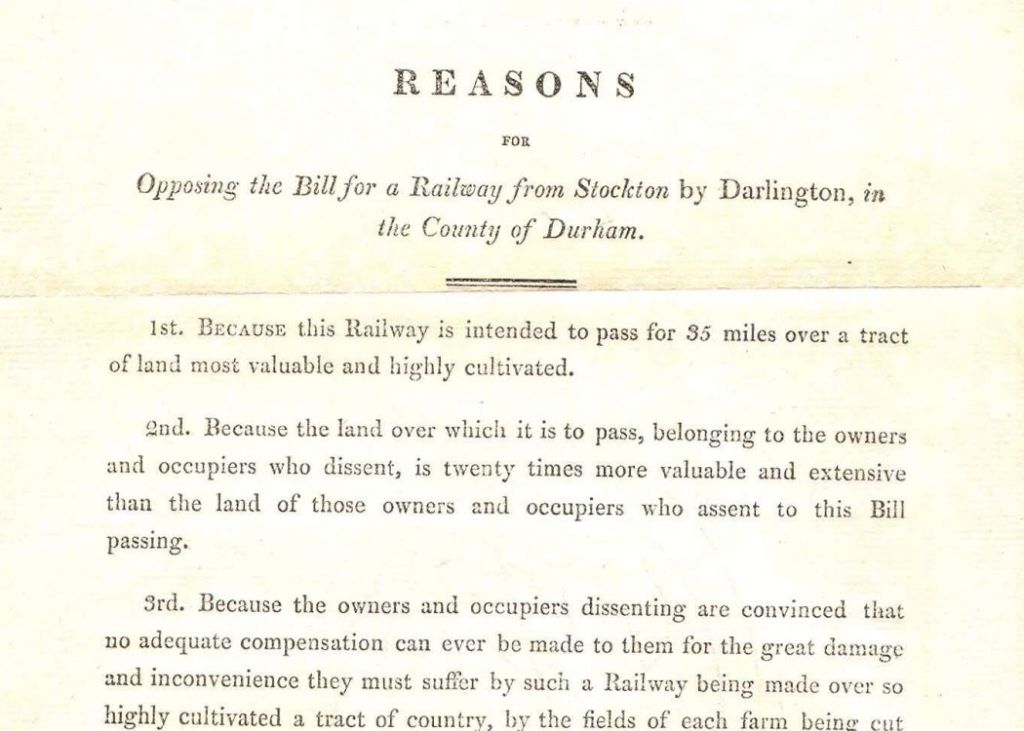

My favourite museum story happily fits the ‘Country Diary’ title for these occasional notes. We learned that it took three concerted attempts over many years to get the Stockton and Darlington railway up and running. At its heart was the struggle between the inherited wealth and influence of the landed gentry and the new money of the non-conformist urban business elite.

Henry Vane, Earl of Darlington, resided at nearby Raby Castle, the centre of his great estate. A fanatical fox hunter who maintained two packs of hounds, he was determined to stop ‘bankers, merchants and others wishing to employ money in the speculation’ from ruining his sport by running their rail road through his fox coverts. He and other country landowners successfully led the opposition in parliament to defeat the initial proposals. A contemporary petition, drawn up by a top London law firm for anonymous clients, makes fascinating reading. It objects to the railway proposal as being ‘harsh and injurious to the interests of the county through which it is intended to pass’ and will ‘spoil lucrative arable land’ splitting profitable holdings in two and be ‘detrimental to the profits of the turnpike road’ running parallel with it.

In March 1819 Quaker banker and line supporter, Jonathan Backhouse, got wind of a plot by the earl to bankrupt his business and so de-rail the financiers. Back then a bank’s promise to pay the bearer on demand the value of a note in gold inspired the disgruntled aristocrat to get his tenants and associates to turn up on a set day at the bank to demand just that. The resourceful Backhouse immediately took flight to London and had a whip round with other Friends in finance, loading the loaned bullion into his carriage and returning at fast as they could back up north on the new turnpike roads to Darlington.

He made it as far as the river crossing at Croft, three miles short of home, when the axle on the hard driven coach broke under the strain. The quick witted banker and his servants redistributed the heavy load and slowly hedged their way back into town, with time to spare, before the Earl’s steward came to call at the bank. Backhouse had raised £32,000 worth of precious metal, more than enough to meet the withdrawal threat. He reportedly saw off the Steward with the words ‘Now, tell thy master that if he will sell Raby, I will pay for it in the same metal’….A great story, which no doubt has improved with re-telling down the years.

The Backhouse family bank prospered greatly thanks to the transformational economic prosperity the railway revolution engendered. Eventually, in the 1890’s, the business would merge with other Quaker founded financial institutions to form Barclays Bank. The bank branch (above) is still there, on its original site in the town centre and about to undergo a refurbishment. Ironically, given the simple design of the original North Road station, this building is a fine example of imposing gothic architecture by Sir Alfred Waterhouse (1864).

Arriving and leaving Darlington via Bank Top – the mainline east coast station (1887) – we’re delighted to see that it too is getting a long deserved restoration. Looking up we take in the heraldic decoration and rhythmic flow of ironwork gracing the roof of this secular cathedral, fitting tribute to a wonderful railway history and the town’s proud role in it.

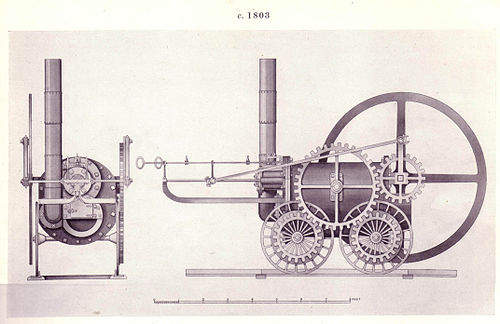

Footnotes: The current ‘Railway Pioneers’ exhibition at Hopetown features superb life size replicas of key early locomotives. One is the unnamed engine (below) invented by Cornish mining engineer Richard Trevithick to transport iron from the Penderryn works in South Wales in 1804. In 2001 I had the pleasure of playing the obsessive charismatic inventor, in the BBC Radio 4 drama, ‘A Magnificent Prospect of the Works’ by Peter Roberts. The action was set in Coalbrookdale, the heartland of the industrial revolution on the river Severn, where Trevithick developed the prototype engine that would became the world’s first steam railway locomotive.

The Friends of the S & D Railway have produced an excellent illustrated introduction which you can download here: https://www.sdr1825.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/stockton-and-darlington-railway-key-facts-booklet.pdf