North to Newburgh on the Aberdeenshire coast for a sight of seals at their ‘haul out’. Grey seals mainly, alongside smaller groups of harbour, or common, seals. They’ve been gathering here at the mouth of the River Ythan in increasing numbers over recent decades. With some 3,000 animals resident at peak times in the winter, it’s believed to be the largest concentration in Scotland.

Impressed at how much work had been done to provide sustainable access to what has since become a tourist attraction. Workmen were extending wooden walkways and some of the lower dunes we passed had been planted up with bunches of marram grass to help stabilise and secure them.

On the opposite side of the windswept estuary is Forvie, a 2,400 acre national nature reserve, consisting of dunes and coastal heath. The southern section is closed to human visitors in the spring and summer to help protect the seals sanctuary. A secure spot too for eider duck to settle, as we spied them now, sitting in a line facing seawards, their dark foliage contrasting with flusters of foraging gulls behind. We delighted to stand watching the seals dive and return, heads bobbing in the wavelets, sometimes turning on their backs to scratch. This safe haven of an estuary allows for the seasonal moulting of adults and their pups to thrive, putting on the weight they will need to survive winter. Some of the seals appeared to follow our progress as we strolled the strand, as curious about us humans and canine companions as we were about them.

A curious landmark on the other shore. The squat concrete bulk of a wartime pill box tipped over, submerging into the beach. Traces of what I assumed was its twin on our side of the water left as a scatter of pitted grey blocks, worn smooth by the waves. Much further south a line of wind turbines traced a line between sea and sky. Further out into the North Sea was a drilling rig while above helicopters plying back and forth from Dyce airport, reminded us of Aberdeen’s importance as a centre of the oil and gas industry and the wealth generated by it.

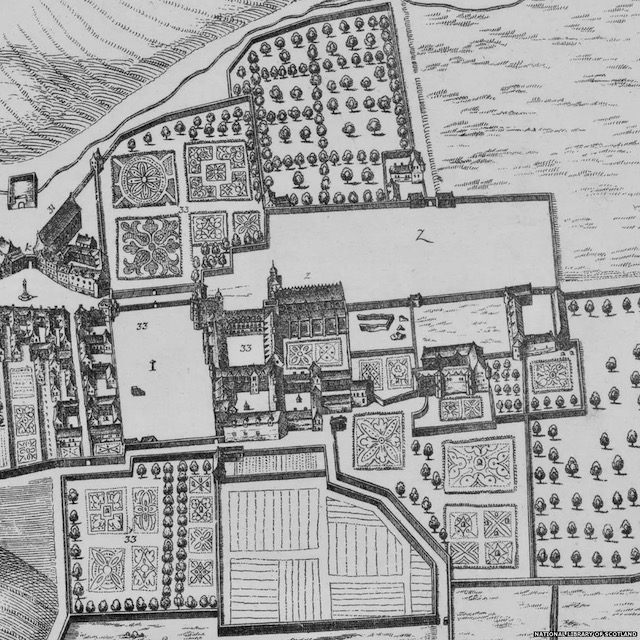

It was wealth of a different kind that enabled the great garden at nearby Pitmedden, our next port of call, to be built three centuries ago. The vision of Sir Alexander Seton, a wealthy Edinburgh advocate, later a judge and MP, and his wife Dame Margaret Lauder in the 1670’s, and built to the designs of eminent Scottish architect Sir William Bruce.

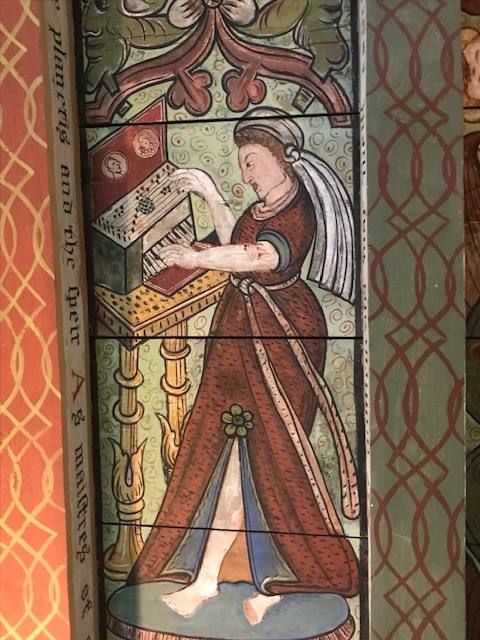

As a Royalist in exile at the Stuart court at Versailles Bruce would have been greatly influenced by Andre Lenôtre’s famous designs for the gardens there. Pitmedden today consists of four great parterres (meaning ‘on the ground’) with another garden on the higher level where Pitmedden house stands. The two levels are linked by grand granite steps with parapets linking elegant stone gazebos at the corners. These square turrets allowed family and guests to congregate for conversation and musical entertainment while looking over the formal gardens spread out below.

These architectural features, along with ancient yews in the further corners, are all that remains of the original garden structure completed in the 1670’s, while the horticultural gem we explored today is a bold modern recreation. When the National Trust for Scotland was gifted the estate in 1952 by its last owner, Major James Keith, it set about the huge task of recreating a formal 17th Century garden from scratch. The original plans for Pitmedden were lost in a house fire so drawings of the old Palace of Holyrood gardens in Edinburgh became the inspiration for the ambitious long term project.

Parterres and knot gardens developed over time to include different types of planting – like including annuals, different types of gravel or using herbs – and the different designs in the modern garden reflect that, alongside incorporating fountains and statuary.

Another contemporary feature is the continuation of installing sculptural forms. Stone pieces from the sculptor James Maine appear at key points around the gardens.

To maintain year long interest and take advantage of the sheltered setting, wide herbaceous borders were incorporated into the new design and most of these robust plants, artfully planted and well maintained, were in glorious full flower on our visit, swarming with bees, hoverflies and other insects.

Impressed by the upper south facing terrace where the stone wall was hardly visible, so thick and dense were the foliage and fruit of the espalier apple trees that have been growing and spreading their boughs there for well over a century. In Major Keith’s day the garden as a whole was producing fruits and vegetables on a commercial scale for the local area’s markets.

The two parterres on the upper level – created in a much more free flowing form – date from the 1990’s and have since been modified in their planting regime with climate change in mind. In 2014 a one acre paddock adjacent to the walled garden was planted as an orchard and soft fruit garden with scores of traditional varieties. I liked the way some apples here are grown as fences, and that bee keepers and their hives are integral to the development.

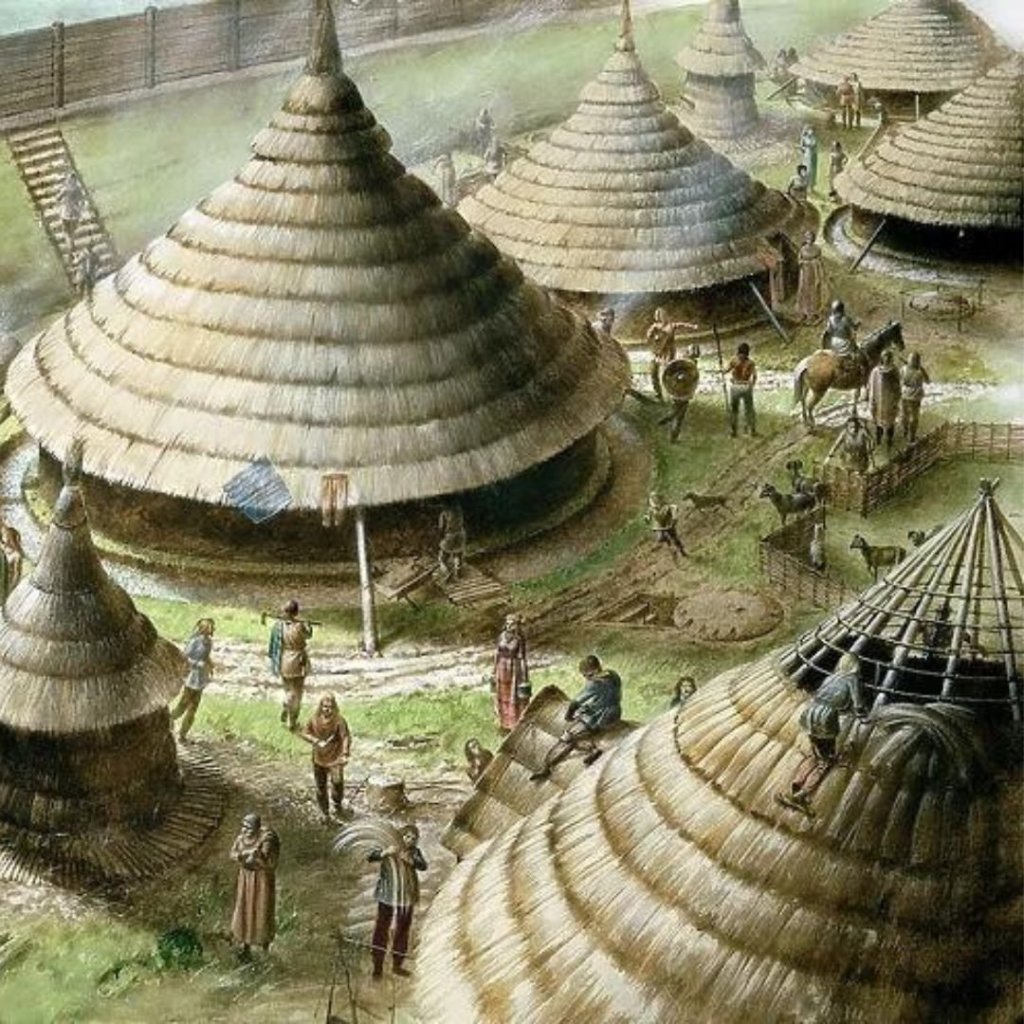

There is also a museum of farming life in the barns, yards and outbuildings. This extensive collection of implements and machinery give one an idea of how labour intensive and demanding a business agriculture hereabouts was back in the day. I particularly liked the recreated farm labourer’s family home in the cottage and the densely planted herb garden, full of fragrant aromas, situated beyond it.