Apples aplenty this year so much time spent recently dealing with the glut. Cookers like Arthur Turner make a great puree, pies & segments slow dried in the Aga before going to store. Most of the crop (James Grieve, Discovery & Katy) grown for juicing means it doesn’t really matter too much what state they’re in when processed.

That’s just as well because birds (especially the blackbirds) make merry with their beaks on the fruit, whether on the bough or the ground. Mice (and I suspect rats) likewise get stuck in once landed. Slugs and insects account for the rest. Wasps though have been notable by their absence this year, which seems odd. Cool temperatures and autumnal winds may have played a part in deterring them.

Not that the resident blackbirds have had it all their own way. Far from it. Going out to empty the kitchen compost bin the other lunchtime I unwittingly disturbed a male Sparrowhawk at its lunch. Caught a few seconds of grey back above long yellow legs and talons as it veered off on the wing. There wasn’t much left of the poor blackbird, just the ripped torso amid a frame of feathers. When I went out again an hour or so later the corpse had disappeared so I guess the raptor must have returned to finish its meal as a takeaway.

Got round to clearing out some gutters and down pipes around house and garage this weekend. A year’s worth of pungent unplugged detritus gave way, nearly giving me an involuntary cold shower. Atop the compression of sludge was a recently deceased mouse. Curious end, climbing high to end up drowned.

The last cut of grass for the year. A satisfying job when complete, as it frames and sets everything off in the garden. The clippings go to the ewes grazing our field or end up under the denser tree cover in one of the copses or sometimes in the compost bins. Just as I was finishing the starter cord got itself stuck inside the engine head cowling. Don’t know how that happened but luckily no hurry to fix it as the machine won’t see any more action now until next Spring.

Our contractor did a good job on the serious mowing in September, clearing the meadow and raking all the vegetation off so little nutrient waste was left. Very pleased with the spread of yellow rattle this season and only hope that continues next year, as their semi-parasitic action weakening the coarse grasses will help make room for other meadow flowers to grow. Was less pleased with the appearance of molehills. Our late mole catcher Jim had inducted me into the craft and when he retired left me a handful of old half barrel traps. Using them in the meadow and lawn however made no difference to activities of my unwelcome subterranean visitors.

I called by a garden centre and bought a batch of the new style clipper types (pictured) and these proved effective. Easier to set physically and you know when they’re triggered as the handles remain above ground. By trial and error, setting and resetting I eventually caught two, in different places, and have had no trouble since. I hate killing these poor creatures and if other non-lethal ways to rid the garden of them worked I would opt for them. I let them do their thing in our field but once they cross the boundary into the garden it’s all out war.

Moles are voracious eaters of earthworms, disabling their prey and storing them captive in a chamber for eating later. The bulbs we plant in the meadow are safe from them (though not from mice or rats). Growing up in Canada Kim has a fondness for Camassia – the North American wild hyacinth – and we were both very impressed with swathes of this tall blue flowered beauty in the meadow at Yeo Valley organic gardens in Somerset when we visited one late Spring pre-Covid. We’re seemingly doomed to disappointment here as our corms rarely grow more than a foot or so in the meadow. We think it humous rich and well drained enough but clearly the camassia has other opinions. Still, hope the chunky bulbs planted this weekend will prove the exception.

Late flowering blue varieties of clematis and a bed of Michaelmas daisies make for cheering sights at this time of year when most other blooms have passed. Especially when so many insects, bees and butterflies feed on them.

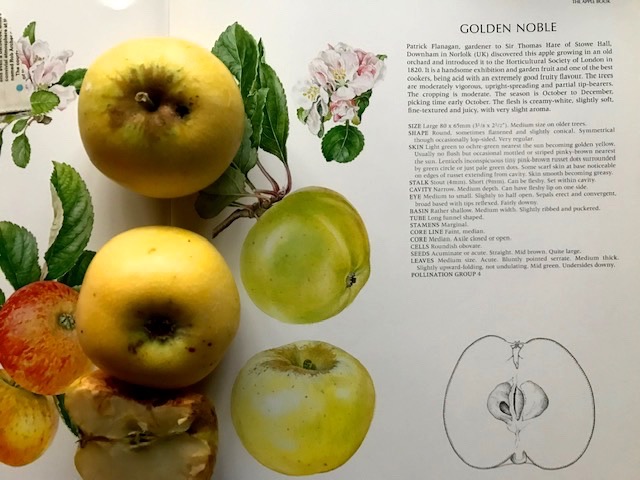

Good cropping on the apple front and the first time we’ve had a proper fruiting from our stout little tree in a tub, gifted by friends, and rejoicing in the name of ‘MickandGrace’. None of us knew what variety it was. Separate threads of homework however declared our apple to be a Golden Noble, an old Norfolk variety of cooker. Grace had grafted the tree on a course at the National Trust’s garden at Acorn Bank in Cumbria and her tutor there helped pin the variety down from a photo I’d sent of the fruit. Our own source was a fabulously authoritive volume I’d been gifted by Kim – The RHS Apple Book.

It’s also been a grand year for the damsons. Our main tree, a Shropshire Prune variety, has shown vigour in its spread, matched this year at least by the cropping. Bagfuls have been gifted to friends or turned into jam. Best of all lying like sunken treasure in a sea of sweetened gin, gently infusing it with unmistakeable flavour, to help us through the coming long dark winter nights.