Recently returned from a week’s holiday in the valley of the River Vouga, mid-way between its outlet at Aveiro on the coast and the city of Viseu near its source in the Serra Lapa.

Like the other major rivers of Portugal The Vouga runs its 148 KM course from east in the mountains to the Atlantic in the west. It was once a major transport route for countryside produce; from wines, granite, metals and timber to fruit and other agricultural produce. (In the 17th Century most of their oranges were exported to England) By 1913, a train line had replaced the inland river boats, which in turn gave way to EU funded new roads that twist and turn above the Vouga’s sinuous green waterways. We enjoyed three separate outings sampling distinctive phases of the river’s flow and topography.

Took a fun day out to swell the ranks of other tourists milling around ‘The Venice of Portugal’, as the city centre of old Aveiro is dubbed. A major port in late medieval times it later became famous for commercial salt abstraction, fishing and seaweed harvesting.

The extensive lagoon and dune ecosystem of the Ria de Aviero, as this estuarial stage of the Vouga is known, now enjoys international status as a major bird sanctuary, home to some 20,000 overwintering wildfowl, the most photogenic of which being pink flamingos.

Trips around the centre’s canal system are a must and the colourfully decorated flat bottomed barges – Molicheiros – that once carried seaweed, salt and general goods now carry human cargo on 45 – 60’ guided excursions.

Unsurprisingly, the last fishing lofts lining the canals have finally closed and are being developed into luxury waterside apartments.

Back on land we visited an Art Nouveau house, now a museum with fine decorative detail, one of many tasteful villas that reflect an early C20th era of increased wealth and pride amongst its leading merchants.

The other end of the Vouga could not be more different. Foreign tourists like us were in short supply here in the mountains, probably because of the limited visitor attractions to lure people up from the popular coastal strip and dangerously high summer temperatures. The Upper Beira region suffered badly last September from wildfires, causing evacuations and widespread disruption, and we sensed a nervousness even now, lest they return.

We stopped off at the Ribeirado dam and looked along the 14km long reservoir it created. It was built earlier this century to supply hydroelectric power, ease flooding and increase scarce water reserves. The road runs along the broad arc of the high dam wall, the power station and its infrastructure far below, where the river re-emerges. With the sheer valley walls either side the whole presents as a peerless study in concrete.

The brightest objects encountered in this uniformly grey spot were the red, blue and yellow recycling bins in the car park. Ominously, the control tower in the reservoir emitted flashing light and warning noises every few minutes. If this location were to feature in a future James Bond film or dystopian TV drama it would not surprise us. A perfect setting of its kind.

Another day we walked the middle reaches of the river. Was keen to access an upper trackway I’d clocked above the road while driving to our holiday accommodation nearby.

As suspected this was once a single track railway. Built just before WW1 it closed in 1980 and its repurposed state, the former Vale Das Voltas line offers superb viewpoints of the valley.

Our parking place by the road revealed a picnic table made from a single slab of local granite set under the awning of a mature horse chestnut tree. Masses of richly purpled convolvulus – bindweed – curled around the wood rails.

The track is understandably popular with cyclists, yet we only encountered four other pedestrians on our amble to and from the route’s spectacular highlight, the Santiago rail bridge at Pessegueiro do Vouga. It’s one of the highest stone masonry bridges in Portugal, with eleven arches and 165m high deck, gracefully spanning river and wooded slopes.

Our walk revealed a stark reminder of last year’s big burn. Blackened trunks and boughs in abundance. A contentious issue in these parts is the preponderance of silvery leaved eucalyptus trees, commercially planted to supply nearby works with biomass and extracted oils. That process is also understood to cause environmental air pollution.

This alien tree, of Australian origin, successfully sustains itself on steep slopes with minimum moisture and burns easily. Eucalyptus rapidly colonises cleared land post fire and is hard, if not impossible, to eradicate.

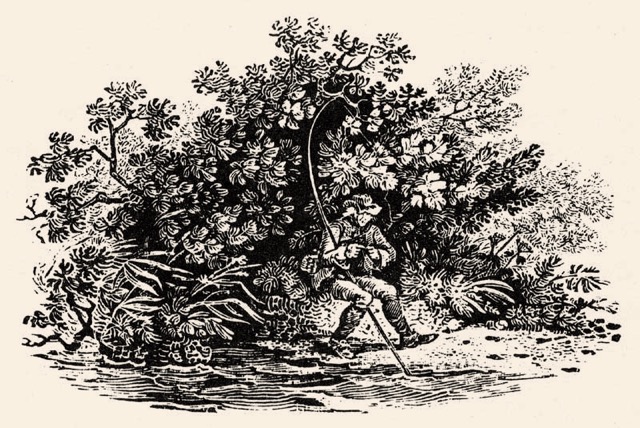

Our walk ended ‘off line’. Carefully crossing the white walled switchback of a highway, we descended to the quiet stillness of river bank and cooling shade of willow and alder that thrive here on its stony floodplain.

This middle stretch of the Vouga is officially designated a ‘Site of Community Interest’. That means minor blockages like weirs that present obstacles for migrating species of trout, eel, shad, barbel, lamprey or mullet are being gradually removed and in some places fish passes are being installed. Otters, birds of prey and many other species of birds and insects are also able to thrive here where human habitation is scarcer.

Delighted in encountering dragonflies and butterflies I waded barefoot in and allowed the hundreds of trout fry mingling in the sunlit shallows to continue feeding and flitting around my feet. A cooling calm end to our lovely lone amble under the afternoon sun.