In an hour and a quarter we are over the border into Scotland and our destination of Galashiels. Glad to sense the place looking brighter and more uplifted than on previous visits 15, 20 years ago. The textile industry was once the area’s biggest employer – as many as 20 mills, mostly water-powered, flourished here at its peak in the 1880’s. Those businesses that remain today have had to specialise to survive and the area remains famous worldwide for its tweed and tartan production. A fitting place then to give a home in 2013 to the peripatetic 21st century popular artwork known as The Great Tapestry of Scotland.

We didn’t quite know what to expect so were delighted to be immersed in what was on offer in the purpose built visitor centre standing proudly in the town centre, which opened in 2021. Having lunch at the friendly café broke down the hours so we could more realistically take in the 160 panel display. It splays across a spacious light filled first floor, depicting Scotland’s story from prehistory to the opening of the new parliament building in 1999.

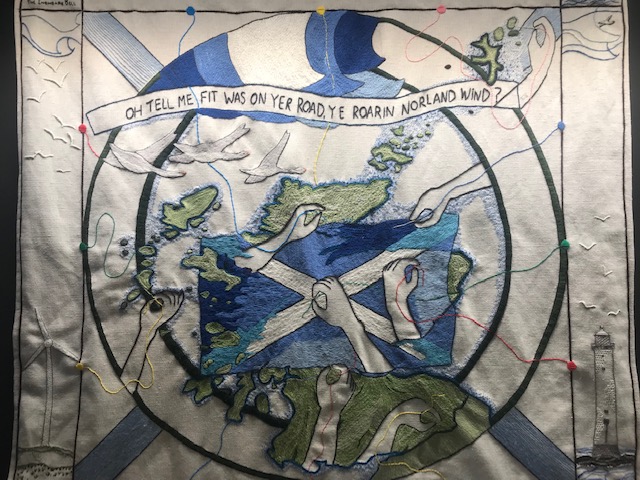

Most panels are a metre/3’ 3” square and because they are not glassed over they appear even more immediate and fresh in their depictions of people, places and events, divided into seven triangular shaped time zones. The whole work stretches for 143 meters/ 469 ft. Informative brief text beneath each work with maker credits.

We are struck by how truly this is a people’s project, reflecting all that’s good in the character of the Scottish nation. A meritorious, interconnected, life affirming achievement. The combined work of a thousand volunteer stitchers in a range of community groups from Galloway to Shetland who put in some 50,000 hours of sewing using 300 miles of yarn. The movers and shakers of this national project were the author Alexander McCall Smith, artist Andrew Crummy, historian and broadcaster Alistair Moffat and head stitcher Dorie Wilkie. Between them they set framework for the stitchers to create and their formidable teamwork got the show on the road – literally!

Having the leisure to view the work in such a wonderful permanent setting opened new perspectives on our neighbouring land. This engaging way of presenting that narrative – of individuals, movements, beliefs through a unique synergy of history, culture and art – makes you wonder what an English, Welsh or Irish equivalent would look like. How would they define and reflect themselves through this form of craft based storytelling?

Scenes of conflict and warfare are vividly played out here. The sacking and pillaging of Holy Island in AD 793 in the Kingdom of Northumbria marked the arrival on these shores of the dreaded Vikings in their dreki – dragon ships. Subsequent colonisation along the Scottish coast saw these remarkably adaptable boats being hauled across narrow necks of land between inlets, giving rise to the place name ‘Tarbert’.

‘Is this a dig at the Bard I see before me?”…One particular panel reminds us how the genius of dramatic licence can run counter to historical truth. The real life Macbeth who ruled in the 11th Century and the character created by Shakespeare to flatter Scots King James 500 years later could not be more different. Macbeth was King of Moray, defeating and killing King Duncan of Alba in battle to become King of Scotland in 1040, ruling unchallenged for another fourteen years. A contemporary source tells of of ‘the red, tall, golden haired one…Scotland will be brimful west and east during the reign of the furious red one’ and that physical description gives character definition here.

Another tableau I liked was the one depicting the Invergarry ironworks. Here in the 1720’s the Englishman Thomas Rawlinson, a Quaker industrialist from Lancaster, encouraged his workforce to adopt a shorter kilt for work purposes. The body wrap style of traditional highlander wear being too encumbering otherwise for industrial labour. A new form of Scottish dress that would eventually become standard wear.

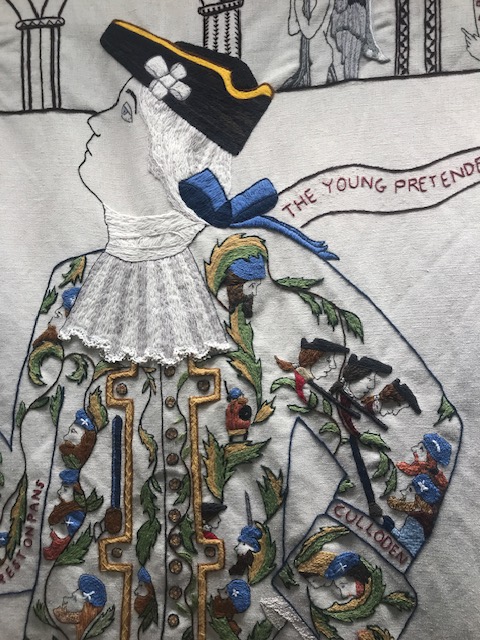

The Jacobite uprising of 1745-6 and Bonnie Prince Charlie’s role in it is a familiar narrative, poignantly and powerfully expressed here in a poignant bitter-sweet design as a ‘vine-line’ linking romanticised landing in Eriskay to final devastating defeat at Culloden.

There’s wit and humour running through the whole exhibition, and that gets more pronounced as the later 20th century chapters unfold with the increasing importance of the arts and popular culture in enriching the national picture, from major festivals to all forms of media .

The exhibition demands a return visit so we no doubt will be back. A great day out for us as borderers on the English side and essential viewing for anyone with an interest in Scots history, art and culture. If you’re planning a visit yourself there’s more info here: http://www.thegreattapestryofscotland.com