We’re recently back from a celebratory weekend away, organised in secret as a gift to share with the significant other. Found a place near enough to drive to easily but far enough away to make for a proper countryside adventure. Some highlights then, as follows.

We arrived in Berwickshire, in the wide valley of the River Tweed and its tributary the Whiteadder, for our stay in the village pub at Allanton. All around the area huge combines, tractors and trailers were cutting, winnowing, baling and carrying off barley and specialist wheat. They continued late into the night, headlights glowing, growling over wide rolling fields with the lanes alive to traffic up to midnight. A fascinating contrast for us who live in the grassy uplands of west Northumberland where log lorries and tipper trucks loaded with gravel for forest roads are the big beasts of rural transport.

We sat out in the pub’s pleasant back garden with a refreshing pint before supper gazing over a scene of blond stubble and waving grain, shadows stretching to far woodlands, the land glowing warm under a setting sun. The Allanton Inn really is at the heart of its rural community. A family run business, part of an ecosystem of small independent local producers and suppliers, proud of their good food offer – from honey and ice cream to meat and eggs – as we were to partake of it. The perfect relaxed hostelry from which to explore this side of the border.

This is a land of big estates and large farms, the metal and concrete barns mostly modern and huge enough to properly house mountains of grain and straw. The population is much sparser now than it would have been in the pre-machine agrarian age. It’s extraordinary to note that within the radius of a couple of miles some of the great figures of the Scots enlightenment were born and grew up. These include the moral philosopher David Hume, geologist James Hutton and botanist and populariser of the tea plant, Robert Fortune.

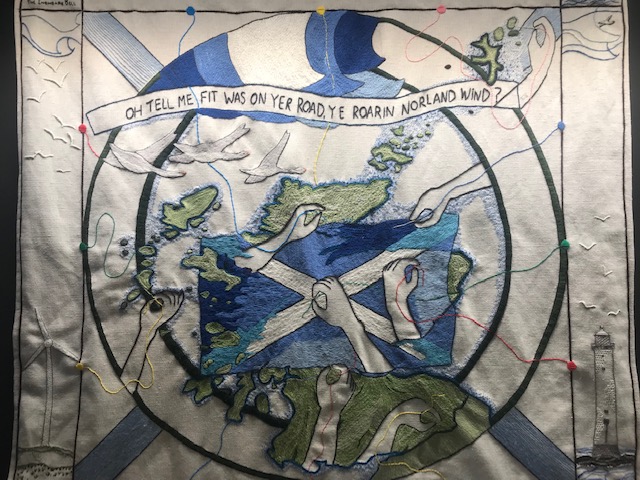

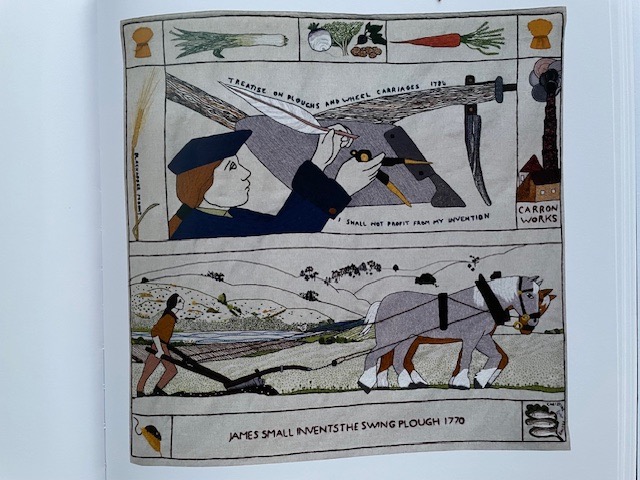

Most touchingly of all is the story of the least known of these worthies and the revolutionary device he freely gifted to agriculture, one that would help fashion the arable landscape around us today. In the 1770’s local engineer James Small used a smithy on the former Blackadder estate at Allanton, using mathematics to experiment on different mouldboards, curvatures and patterns to produce his improvement on the ‘Rotherham’ cast iron swing plough. Previously many men were needed to work teams of oxen to pull a flat wooden plough while Small’s only required a pair of shire horses and a single ploughman to operate. Small even demonstrated his invention to ‘Farmer’ George III and his ‘Scots Plough’ was rapidly copied and developed by others as he not wish to profit from his invention by taking out a patent and sadly died in 1793 of overwork and poverty. Modern day embroiders have honoured his memory as James and the plough feature as one of the wonderful metre square panels in the Great Tapestry of Scotland, on permanent display in Galashiels.

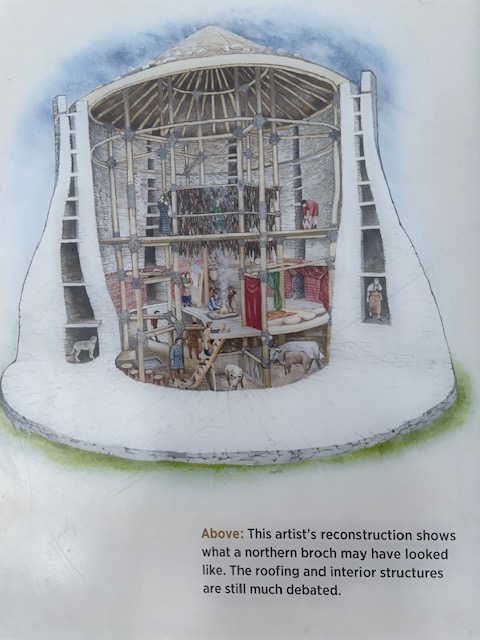

Situated on the eastern edges of the Lammermuir hills, below the lofty summit of Cockburn Law and overlooking a steep valley sits Edin’s Hall Broch. It was the high point of a circular five mile walk we took over fields, through woods, along tracks and heathland paths.

We made two separate crossings of the infant River Whiteadder by ford and footbridge. Summer picturesque as the scene was, one could imagine the place when the waters were in spate. The road sign at Abbey St Bathans reminds drivers of the risks.

Brochs – ancient fortified tower houses – are usually found in the highlands and far north of Scotland so the one here is something of a geographical oddity. Our slow climb to reach it enhanced by seeing male wall brown and small copper butterflies basking in the sun and fluttering ahead as we climbed through swathes of tall bracken.

Dated to the 1st century AD what really lends Edin’s Hall broch a sense of wonder is that so much stone remains to define its walls, wide enough to incorporate chambers and stairs. The centre point gives a 360 degree experience of what was once a whole community’s secure home and stores, standing at least two levels high and probably roofed with timber. Hard by the broch are remains of later hut circles, ditches and ramparts. Awed as we were we couldn’t help wondering though where its inhabitants would have sourced their water supply, with not a spring in sight.

Picking up a metalled lane diving down into the wooded valley bottom we came upon this weathered sign at a hairpin bend. The only thing near a toot we heard on the descent was from the occasional whirr of spokes or tinkling bells as racing cyclists shot by with friendly waves. Like them we appreciated a rest break at the friendly informal tearooms in the old stables of the original village woodyard by the river. We can testify that the home baked fruit scones are superb.

Every few years sees us on a return visit to Berwick. A preamble along the massive Elizabethan ramparts leads literally ‘off the wall’ into the multi-storied Granary gallery, a former Georgian warehouse on the quay overlooking the three great bridges, monuments of different centuries, that carry road and rail links across the great border river.

The retrospective exhibition we’d come to see at the Granary was of the respected artist, teacher and plantsman Cedric Morris (1889-1982). We found it something of a mixed bag. His flower painting, especially of Irises, remain glorious testimony to his knowledge and ecological awareness. The best known self-portrait and studies of Parisian café life in the 1920’s insightful and sensual.

The art that really moved us though was on the seafront across the border at Eyemouth. In October of 1881 a terrible storm wreaked havoc on the Berwickshire coast, and 189 local fishermen were drowned, leaving behind 78 widows and 182 children. The town’s fortunes went into long term decline in the wake of this, Scotland worst recorded fishing disaster.

‘Widows and Bairns’ represents real people, arranged in groups above the name of their boats. Sculpted by Jill Watson and cast by Powderhall Bronze it opened in 2016. We watched visiting families stop and talk about the story. The best kind of public art, rooted in people’s history, powered in this instance by tragic drama to command our attention and stimulate conversation.

In the 21st century, the community here has been embracing eco based industries and sustainable tourism and this attractive harbourside town – like Berwick across the border – seems on the cusp of change for the better. The broader Eyemouth story is well told in the delightful volunteer run museum housed in a former church.

We also enjoyed taking a leisurely stroll along the narrow harbour around the mouth of the river Eye with its working fishing boats, quayside processing plants and local produce stalls. (kipper rolls anyone?) These merge with an array of smart locally based retail businesses (excellent Italian ice creams), the sandy town beach and restored stone jetty with its bright red handrails and fine prospect.

A little further up the rocky coast lies St Abb’s Head, named for a Northumbrian princess who founded a monastery here, now long lost, following her safe delivery from shipwreck. Fittingly a lighthouse, dating from the 1860’s and built by the Stevenson family (who else?), still casts its powerful light from the head. Unusually, it is tucked into the cliff below the lighthouse keepers cottages (now holiday accommodation) as the higher ground above and beyond has always been prone to mist and rain, obscuring vision at sea. Hence the red painted fog horn, seen below.

If we’d been here in late Spring we’d have witnessed the vast flocks of gannets, razorbills, gannets, kittiwakes and other seabirds that crowd the nursery rockfaces and for which the bird reserve is nationally renowned. Their guano, whitening the masses of red blue sandstone rocks, is striking but the birds and their fledglings were no longer in evidence this bright breezy morning in August. Instead masses of house martins dominated the clear blue skies above small bobbing boats filled with visitors tasking in the awesome sea level view of this spectacular headland.

Our return leg, mostly along the single track lighthouse access road, revealed a stunning surprise vista of more cliffs running northwards. Once out of the severe wind tunnel blast between those cliffs and St Abb’s head, the path drew us away into the calm serenity of a narrow fresh water loch in a ravine fringed with reed and sheltered by woods. The National Trust for Scotland run the excellent visitor centre in an old farm complex where we parked to start and finish our wonderfully rewarding four mile trek.