Maybe it’s from watching too much Danish television and cinema, but the northern region of Jutland lodges in my imagination as a cold windswept archipelago breeding outlaws, from Viking raiders to Scandi noir murderers. How refreshing then to set the record straight with a welcome immersion in the luminous world created by one of that country’s most celebrated artists, Anna Ancher.

Last week, on a rain soaked Tuesday morning, we slipped into the serene interior of the UK’s oldest public art collection, the Dulwich Picture Gallery in south London. We’ve previously caught some fine shows here but this one was different in that the artist was hitherto unknown to us.

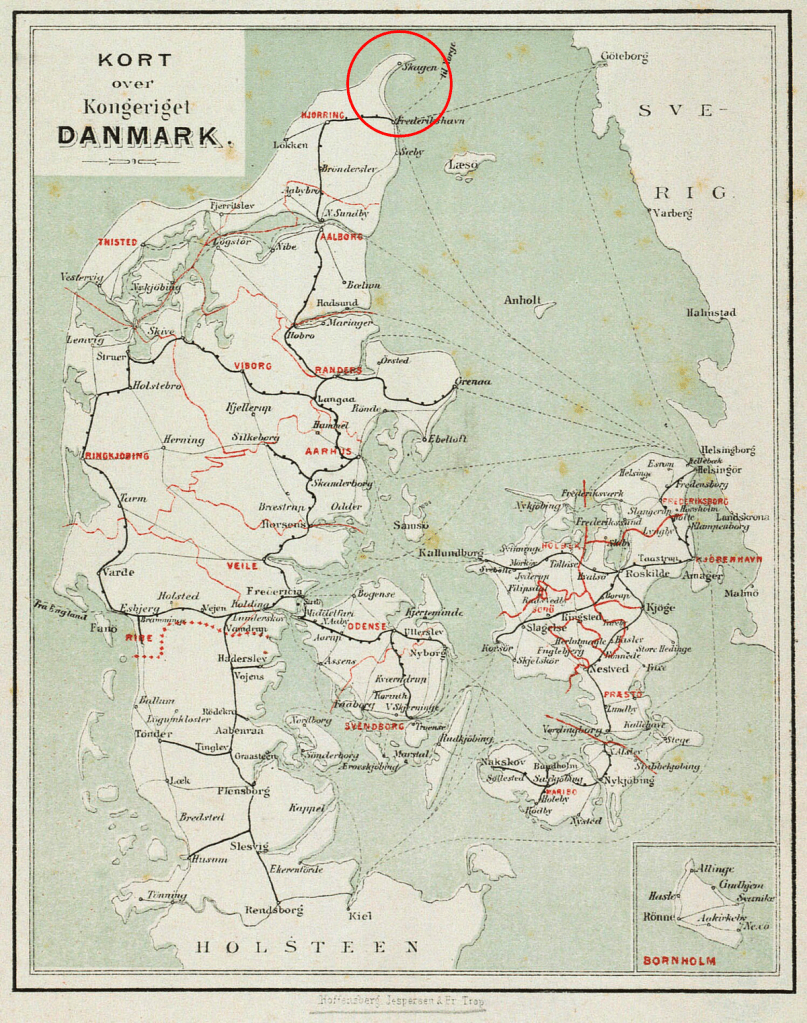

Women artists of Anna’s day – she lived from 1859 to1935 – faced huge barriers in pursuing their careers. Her family, the Brondum’s, ran the only hotel in the remote town of Skagen (pronounced Skay-en) where she was born and spent most of her life. It became a lively centre of artistic activity from the 1870’s and still trades today in what has become an upmarket seasonal resort town of uniform bright walls and red tile roofs.

Emerging artists were drawn then to what was a near inaccessible spot at the very northern tip of Jutland, where the Skagerrak and the Kattegat seas meet. An exposed lone finger of land defined by sand dunes and continual beaches under vast open skies. One of those dynamic young incomers, Michael Ancher, became Anna’s husband and collaborator.

At that time most of the indigenous inhabitants led a hard existence as farmers and fisherfolk and many, like Anna’s mother Ane, were devout protestants. Surprisingly perhaps, Ane supported her daughter by paying for private art lessons in Copenhagen. (Women were banned from the official schools) Later both Anna and Michael studied in France where the liberating influence of impressionism was key to further development.

Anna was not just confined to the traditional female realms of home and family for subject matter and she demonstrated her compositional skills in large scale works like this one from 1903. The Skagen mission church congregation her mother belonged to, seated in the dunes ,listening to a sermon given by their local preacher.

Particularly liked this little picture of mothers bringing children to be vaccinated against smallpox. The practice had been compulsory in Denmark since 1810 but then, as now, it was a cause of controversy. With Michael modelling as the doctor, alongside local women and children, clearly shows which side of the argument the Anchers favoured.

Another eye catching small study in oils shows the Ancher’s daughter Helga, with Anna’s cousin Ane Torup, dressed in green, at home on the bench in a summer garden (c.1892).

Farmland had been painstakingly reclaimed from sandy heath and this vibrant close study of harvesters in the corn from 1905 both focuses and intensifies the colouration of the scene, where the sturdy workers set out to reap the rewards of their year’s labour.

One of the major oil paintings on display is a wonderful portrait from 1886 of a maid in the kitchen which demonstrates Ancher’s particular genius. A fascinating composition imbued with intimacy and stillness. Entrancing in its luminosity, with echoes for me of Vermeer.

Thank you Dulwich for bringing us this cultural gift from rural Denmark. I for one will – literally – see that land in a rather different light from now on. The exhibition continues to 8th March. https://www.dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk/whats-on/anna-ancher-painting-light/