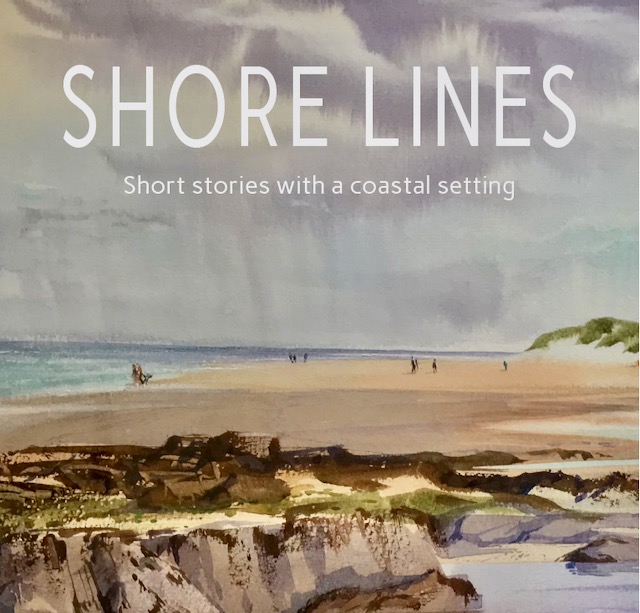

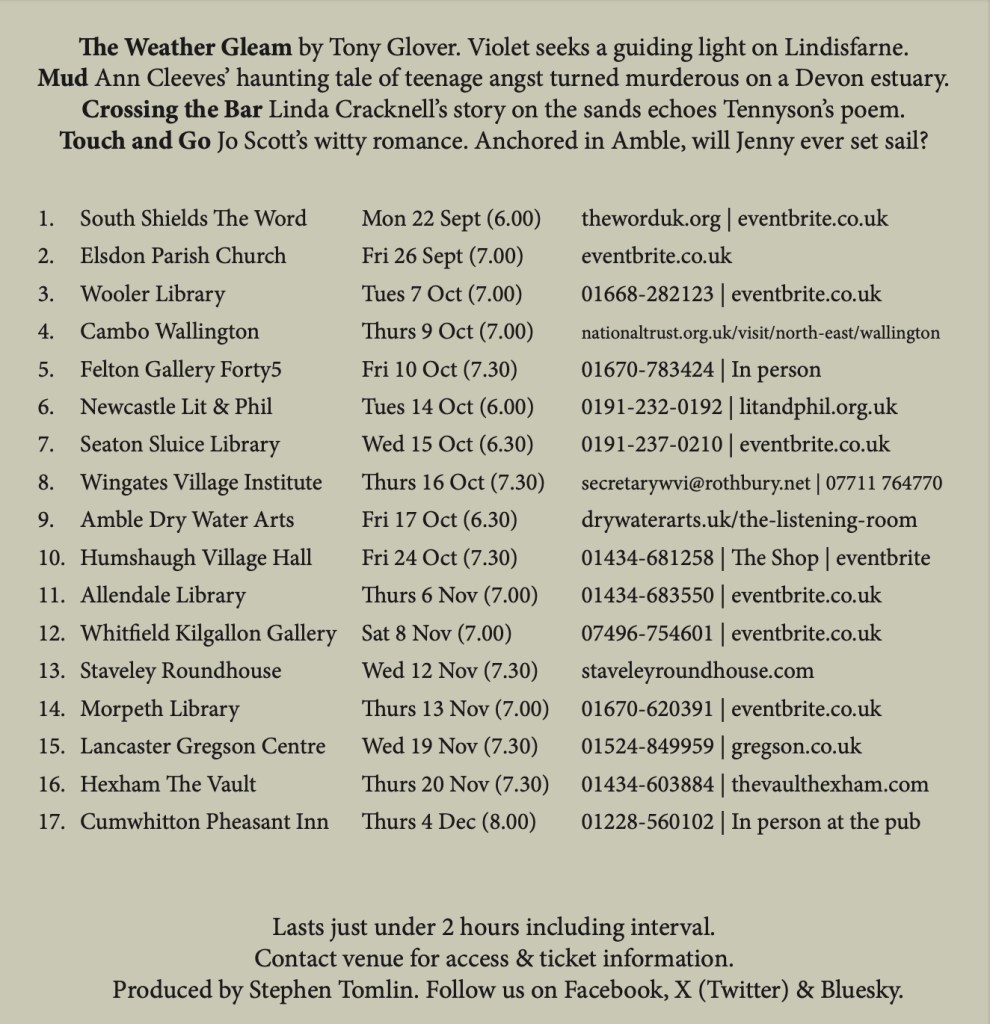

Experienced the usual emotional mixture of pleasure and relief that this year’s ‘Shore Lines’ tour for The Border Readers had ended earlier this month. A pub’s not a bad place to come to the end of the road in and The Pheasant at Cumwhitton in the Eden valley is an exceptionally warm and welcoming hostelry.

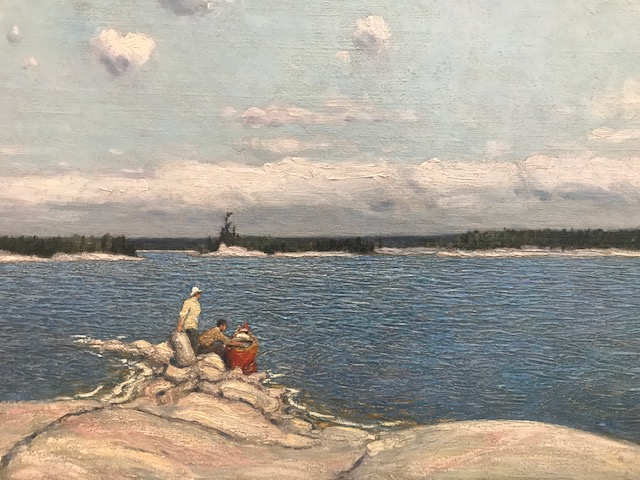

The function room upstairs set out with tables and chairs proves the most intimate of surroundings for this final gig for myself and fellow readers Grace and Wynne. A bonus in having writer Linda Cracknell and her partner Robin with us. Linda’s short story, ‘Crossing the Bar’ was originally commissioned and broadcast by BBC Radio 4 in 2018, and was inspired by Tennyson’s classic poem ‘. I picked them up earlier from Armathwaite station on the fabled Settle – Carlisle line a few miles away. A beautifully preserved Victorian village station, wreathed now in a swirling mist, my friends the only passengers getting off here, who were more than pleased to see me emerge from the gloom. Very atmospheric indeed.

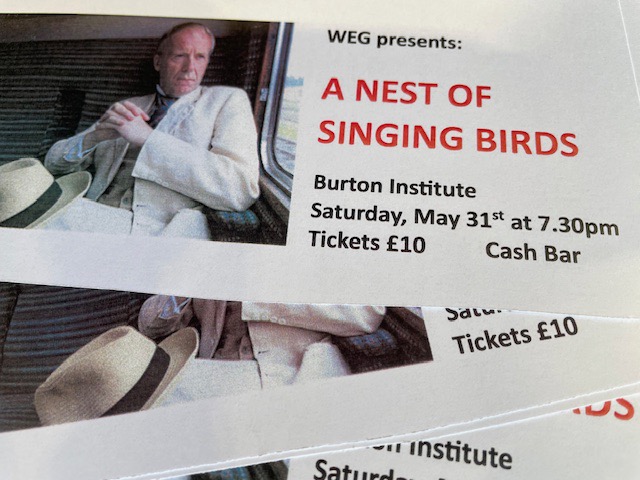

Other highlights of the tour included a sell-out debut at The Gregson Centre in my former home town of Lancaster. A lively celebration, with family in the audience and readings shared with old pals and demi-paradise associates, Roberta and Helen. I use to captain the Gregson bar’s ‘B’ team, part of the city ‘s pub quiz league, so it’s a place dear to my heart.

I always assume our annual themed literary event to be a cost neutral production but this year, to make sure I was not kidding myself, I crunched the numbers and, lo and behold, that was indeed the case. Those calculations make no account of hours spent as producer – this is after all a retirement passion project – but in every other way it continues to pay for itself as a non for profit community based cultural venture.

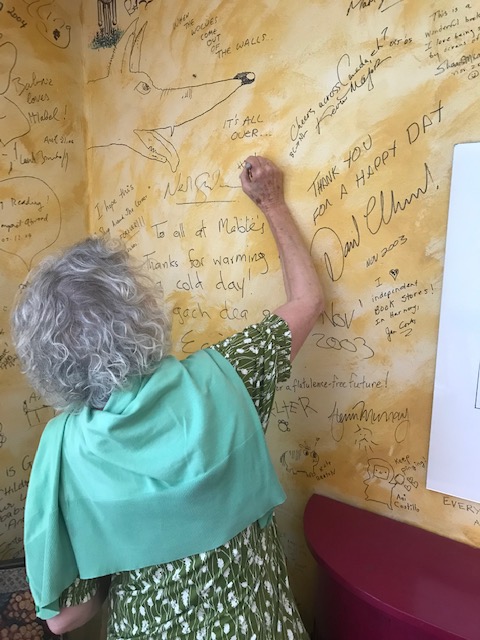

Caught ‘Miniature Worlds’ the latest exhibition at the Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle a few weeks ago. It explores the intricate beauty of small-scale landscapes across three centuries of British art. (Intro at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dgQf9zt3x7o&t=59s) There is work by Thomas Bewick (1753 – 1828) a particular favourite, thanks to my association with Cherryburn, the farm which was his childhood home in the Tyne valley, and which I’ve written about here in the past. Bewick’s exquisitely executed borderless wood cut vignettes and ‘tale pieces’ that accompanied his text about birds and animals he depicted were hugely influential in both artistic and natural history terms.

Other favourites took me back to an early love of literature gained through the great childhood classics, like Jon Tenniel’s unforgettable illustrations for Lewis Carol’s ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’.

And who can resist Beatrix Potter’s charming animal character studies in watercolour for those love-to-handle little books published by Frederick Warne in the early C20th.

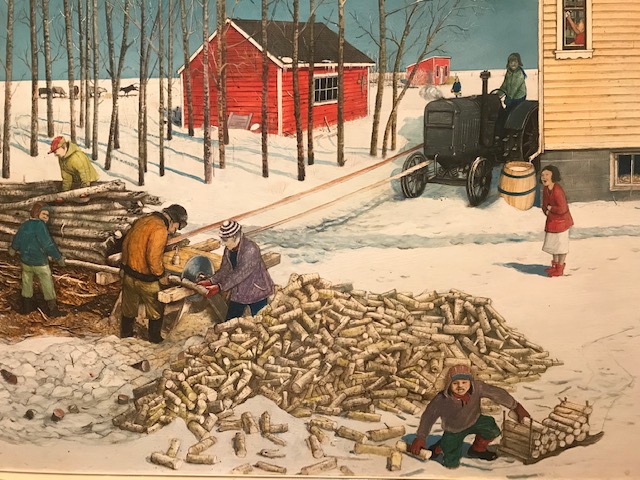

The countryside around lies dormant now but the play of weather over it never ceases to impress. The changing climate has brought with greater unpredictability, with milder winter days and heavier rains. Bare branches reveal last year’s tiny nests of moss, feathers and grass.

Gardening tasks undertaken when weather permits include clearing banks of dead foliage, starting to prune, nourishing compost heaps, fishing surplus leaves from the ponds. With the help of a neighbouring friend, who brought his leaf blower to push the necessary oxygen, we had fun setting a bonfire in the field with cautious use of petrol to ignite the damp mass.

Neighbouring farms’ cattle and sheep are rotated around sodden pastures. My eye caught by the substantial red metal creep feeder which allow the shorthorn herd’s calves dedicated access through metal bars to get their fill of hay. A foretaste of Spring and the lambs to come. Flocks of ewes graze, rumps raddle marked by tups in harness. A Suffolk lords it in one neighbour’s field, A Texel in another and an old favourite from past years, Southridge’s Border Leicester in the field opposite us. BLT I call him. He’s always fearless and inquisitive when we meet so suspect he’s been used to handling from an early age. Curiously, there’s no harness on him, but has obviously been hard at work.

Bumping in to friends out and about we are related some hairy tales, disarmingly told with great humour. One person, out walking on remote hills to the north of the county succumbs to a heart episode caused by arrythmia which floors him. Ringing 999 he’s told to text a number. Rescue services precisely locate through GPS and a stand by air ambulance helicopter is swiftly dispatched to hoist and whisk him away to hospital in Berwick.

Our egg supply is down. The neighbour who supplies them says a badger dug a tunnel into the coupe overnight and wiped out over half the hens and ate what eggs it could find too.

A walk over the fell leads us to an artistic friends household selling home-made artefacts for Christmas, all on display in a cosy made-to-order shepherd’s hut next their cottage. We pop into the kitchen to pay and are invited to stay for another hour or so for a long overdue laughter loaded catch up over coffee and home made mince pies.

There’s a nearby lane, along which the long distance trail runs, narrow and undulating with dry stone walls, trees and shrubs either side. It boasts a good crop of haw berries popping red against a thick crusted layer of lichen. Benefits of not cutting back means a vital food source for birds while the presence of the lichen proving pure air quality in these uplands.

Kim in a flurry of home baking and making for Christmas so really looking forward to sampling what’s on offer. Here’s our Christmas best wishes to you and yours. Look forward to having your company on this occasional country diary page through 2026!