Bound by near roadless swathes of borderland conifer forests to north and east, Hadrian’s Wall and the Longtown Brampton road to the south and the Carlisle to Hawick A7 highway to the west is the remotest corner of Cumbria. Running right through it, to join the tidal border Esk at the Solway, is the River Lyne. Its rapid peat filled waters cut a snaking course through sandstone and its steep banks and remote location have earned it the touristy teasing title of ‘Hidden River’. Lyne in Gaelic means pool or waterway and there are numerous other rivers and lakes with Lynn or Lin in their names scattered through the north and west of the country.

A few years back an enterprising Cumberland dairy farming couple designed and built log cabins on their land here overlooking a particularly attractive stretch of the Lyne. Later they added a log barn for weddings and other events plus a log built restaurant with picture windows and wood burning stoves. In partnership with a resident local chef they set out to woo residents and tourists alike with eclectic, hearty and imaginative menus. A rave write up by Carlisle born reviewer and broadcaster Grace Dent helped boost their reputation nationwide.

Last weekend our Cumbrian based friends invited us over to help discover both food and location on what turned out to be the first official day of spring. Getting there in the first place was a challenge due to the perils of navigating unknown winding lanes through what Ms Dent in her review dubbed ‘miles of rolling green nothingnesss’. We eventually made it and enjoyed a superb Sunday lunch in good company.

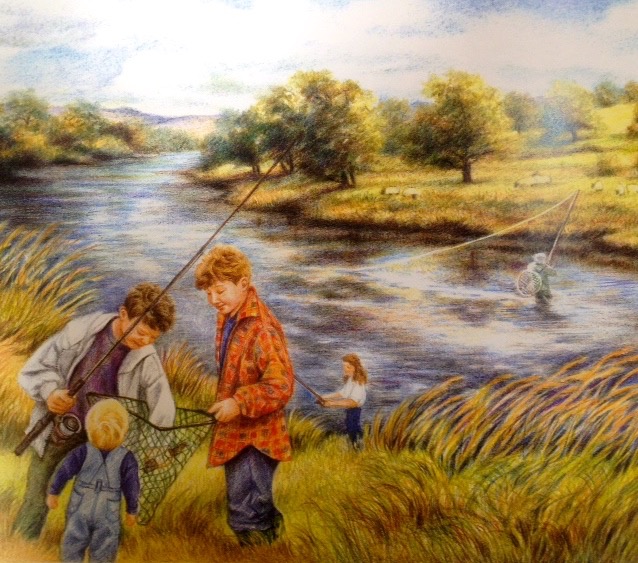

Three hours later, replete and needing that promised exercise, we set off upstream to walk a circular four mile section of the hidden valley.

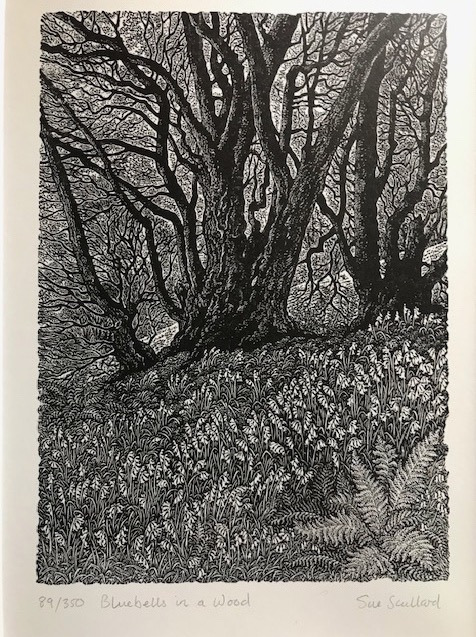

Parking at Stapleton village hall we cut across particularly boggy fields (it had rained prodigiously the day before) before descending to the river Lyne, heard before seen, in dense tree cover. Ferns thriving in the cruck of tree branches and beds of moss on bark and stone indicates the dampness levels here through most of the year.

An elegant footbridge spanned the river, proudly displaying its makers seal. Our journey the other side soon brought us to steep sided former coppice woodlands bisected by a series of rivulets, which made progress along the indistinct muddy path potentially perilous in places.

We eventually emerged at height among mature broad leafed trees which gave a fine view over meadows cupped in a wide bend of the river where Roe deer were grazing. Our presence caused them to make their escape, white tails bobbing furiously, with prodigious leaps over fences and hedges.

More woodland slopes with celandine, dogs mercury and dense mats of a dominant ground hugger I later discover is Greater Wood Rush, a shade loving plant of acidic soils well at home in woods. We eventually came to a farm housing cows & calves, perched on the valley edge, with an organic side line, growing fruit and veg in a brace of polytunnels.

Soon we came upon a cottage with a tidy kitchen garden and poultry in the dell where a side stream entered the Lyne. The cheery householder was burning wood and waste while his geese were living up to their reputation as guard animals by escorting us through their domain with a chorus of honks.

Now back on a concrete access track we could see through the bare trees where the two feeder branches of the River Lyne – termed white and black – converge. A lifebelt indicated a swimming spot in the newly widened waterway. I smiled to see a butterbur, which so loves damp spots, poking its purple coloured flower heads above the soft ground.

The track joined the public highway where we turned back to cross, in turn, both branches of the exuberant young river. Curious to note the long extended stone walled parapets of the bridge. Indicated to us this design must act as a barrier to the road getting flooded.

Following the lane up we climbed steadily out of the valley back into the undulating pastureland. Sheep and ponies, thinking we were carrying fodder, tracked our progress and piled in at gates as we passed in hopes of sustenance.

My walking companion, who knows these things, pointed out the ‘Cumberland dyke’ structure of road verge hump, drainage dyke, bank topped with hedge. This stretch was nicely maintained for good off road drainage with primroses and wood anemone emerging along the sheltered bankside. Who doesn’t love these early spring arrivals? Anemone an indicator of ancient woodland, vegatively slow spreading, delicately beautiful and the ‘prima rosa’ living up to its name.

At the incline’s T Junction another fine old Cumberland County Council road sign greeted the eye. Turning right here on the home stretch brought us along what must once have been a drove road. It ran long and straight with wide verges for cattle to graze as they made their journey from the borders to markets in Carlisle or Penrith. We passed on our left an old building which was once a pub, where drovers and countrymen could slake their thirst, but is now a private house.

After bidding adieu we followed our friends car out of the area, glad for the guidance and happy to have discovered more about an out of the way place not so far from where we live but in other ways a seeming world away. A week later and I imagine the flowers we saw emerging will be well on its way to greet the spring in their hidden valley homeland.