‘The most rebellious town in Devon’. That’s the defiant legend of Colyton in East Devon. One of the first Saxon settlements in the county, the town’s street patterns reflect that period but sadly we’d little time today for further exploration as our friends, with whom we were staying in nearby Lyme Regis, were taking us for a ride. Literally. But first, a bit more about that proud boast…

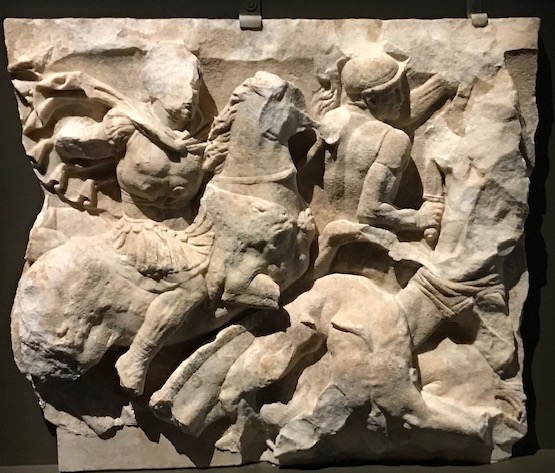

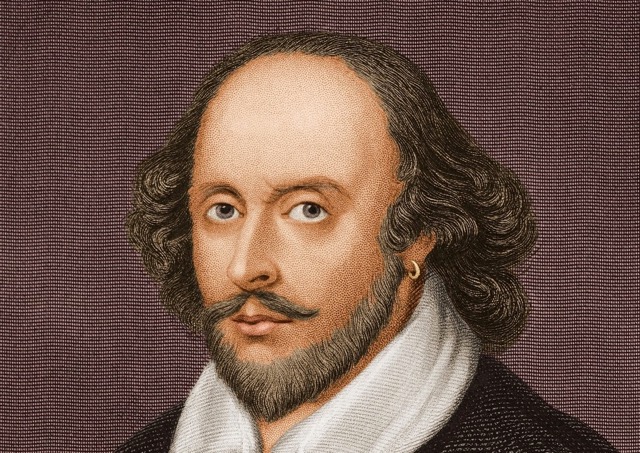

Charles Stuart was already father to a two year old boy when he turned up at Boscobel on the run after his army’s defeat at Worcester in 1651, the incident I wrote about in the last but one country diary. That child, James, that the teenage prince had by his first known mistress Lucy Palmer, would be the eldest of fourteen illegitimate children the ‘Merry Monarch’ would father in his lifetime. Following Charles II’s restoration to the throne, the thirteen year old was given the title of Duke of Monmouth. Later that same year, 1662, he was married to Anne Scott, 4th Countess of Buccleuch, taking her last name and additional title of Duke of Buccleuch. He then had a successful military career, winning key battles and becoming the poster boy for protestant populism. (Interestingly his Buccleuch descendants are one of the richest aristocratic landowning families in Britain today).

Touted as Charles II’s protestant successor, Monmouth attempted on Charles’ death in 1685 to wrest the throne from his catholic uncle James, duke of York. Landing at Lyme, Monmouth issued a declaration accusing James II of poisoning his father, usurping the throne and ruling against the law. The West Country, with its strong protestant sympathies caused many to flock to his colours. Colyton excelled itself in contributing 105 men to the righteous cause, more than any other town in the region, hence the soubriquet.

The Monmouth rebellion came to a tragic end when James II’s professional army ruthlessly crushed the largely untrained yeomen insurgents at Sedgemoor on the Somerset levels – the last full scale battle fought on English soil. Monmouth fled the bloody scene, but unlike his father before him, failed to secure help in escaping to safety abroad. Apprehended by pursuers in the New Forest just days later, Uncle James showed no clemency and Monmouth was publicly executed for treason in London. (An awful botched job, taking five attempts by the executioner to part head from body)

The ‘bloody assizes’ held in towns across the western counties in the wake of the failed uprising was presided over by the infamously sadistic Judge Jeffries. He sentenced hundreds of wounded and captured rebels to be hanged and hundreds more to be transported for life to the plantations of the West Indies, and many unfortunate Colyton men were amongst those so punished. Three years later the ‘Glorious Revolution’ led to Protestantism’s new aristocratic champion William of Orange overthrowing his father-in-law James II, who subsequently fled into permanent continental exile.

Nearly 330 years later we are amongst the thousands of visitors who associate this area less with tragic rebellion and more with fun rail trips on heritage trams. The Seaton tramway runs along narrow gauge lines for over three miles through the lower Axe river valley, from Colyton to the seaside resort of Seaton on the UNESCO designated Jurassic Coast. On the way the track crosses a busy road and passes two nature reserves, home to many species of wading birds.

The colourful, immaculately preserved collection of heritage trams was started in 1949 by engineering entrepreneur Claude Lane. Previously run as seaside attractions in North Wales and Eastbourne the trams found a permanent home here on the former rail branch line. Closed under the Beeching cuts in 1967 it reopened as a tramway in 1970, and has gone from strength to strength ever since.

I was impressed by the purpose built modern terminus at Seaton as well as the modernised 1868 original railway station outside Colyton, at the other end, where we enjoyed lunch on the platform. The joy of this sunny afternoon outing was the fab half hour ride on the top deck down to Seaton. Wonderful all round uninterrupted views you only get seated on the open deck, with the return leg a sheltered more sedate experience on the lower deck.

Viewing trams approach on the other line, watching the freshwater river merge into its tidal estuary on one side and taking in the marshland nature reserve with its hides, wooden walkways, reedbed marshes and shallow lagoons on the other. Another West Country attraction experienced. Long may it continue to bring smiles to the faces of all who travel on these beautiful engines, young or old.

Footnote: The Monmouth Rebellion had been my chosen subject back in 1990 when I was recovering from industrial injuries sustained on a theatre tour and decided to fill in the time by applying to compete in the next season of ‘Mastermind’ on TV. The BBC production team said there wasn’t enough information on this topic for their QMs to set questions so I was reluctantly persuaded to drop it. They used the same argument about my subsequent choice of ‘Dartmoor and its Environs’ but I stood my ground and they gave way…A successful rebellion, as I went on to win that round of the competition.