Easter in the Lake District, and a happy few days staying at a favourite vegetarian B&B between Hawkshead and Tarn Hows. A short drive away is a place I’ve been meaning to visit for years, Wray Castle on Windermere. In the care of the National Trust since 1929 this high Victorian romance of a building was at the centre of a mock baronial estate enjoying extensive lakeside frontage with large boathouses, while inland a farm, church, vicarage were built. The farmland and ancient woodlands also included Blelham Tarn. We set out on foot to link all these places up over some 3.5 miles.

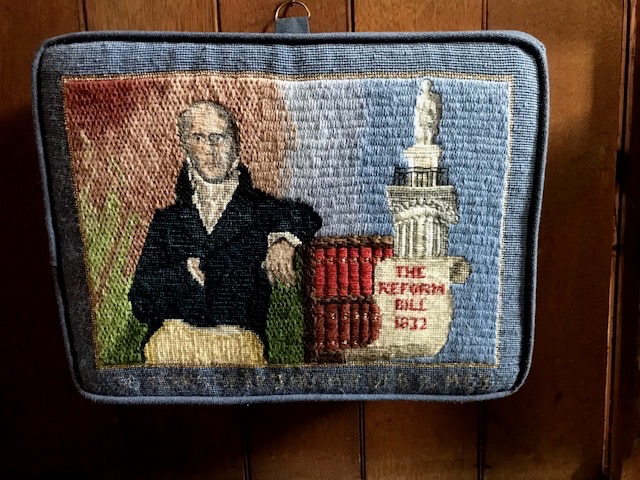

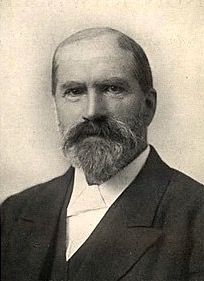

Wray Castle and its estate was built between 1840 and 1860 by a wealthy Liverpool surgeon James Dawson and his heiress wife Margaret as their Lake District retreat. The interior’s grand rooms are now bare but would have once been lavishly decorated and furnished. After the Dawsons had both died the castle was occupied by various owners. In the summer of 1882 the wealthy Potter family from Kensington booked it for the summer, their first visit to the Lake District. The Reverend Hardwicke Rawnsley, the Vicar of Crosthwaite nr. Keswick who also held the living of St Margaret in the estate grounds, befriended the two children, Beatrix and Bertram. Rawnsley encouraged Beatrix to publish her first book, The Tale of Peter Rabbit, in 1902. A key influence on her, and the epitome of ‘muscular Christianity’ the energetic and charismatic Rawnsley was a leading Lakeland conservation campaigner who would go on to be one of the founder members of the National Trust in 1895. The money Beatrix Potter earned from stellar book sales during her lifetime enabled her to buy scores of farms and other property in the Lake district. Left on her death in 1943 to the National Trust, this extraordinary endowment became the core of the organisation’s extensive holdings in the region.

Setting out on the road that got us here we’re glad to leave it and take the dedicated walking/cycle track running parallel in the field. We pause to admire an old metal field, typical of a grand Victorian landed estate like Wray Castle.

We circumvent the tarn, only bordering its shores a little way, wending through open woods with some ancient oaks, past a slew of slates where a wall has been recently broached, before heading uphill on a well worn stony track. Not clear whether the winter’s storms had brought a tree down to smash the wall but, as elsewhere around the country, the land is littered with tree trunks and here, if not blocking paths or roads, are left to lie and decay for nature’s sake.

An iron age sword, a rare discovery in Cumbria, has been unearthed near here. The weapon had been deliberately broken in half, prompting speculation it was part of a burial rite or a ceremony by a chieftain to claim an area of land. Looking back on the mirrored waters we see a scientific measuring station floating on it, maintained by the Institute of Freshwater Ecology whose HQ lies on nearby Windermere at Far Sawrey. (It was previously housed in Wray Castle).

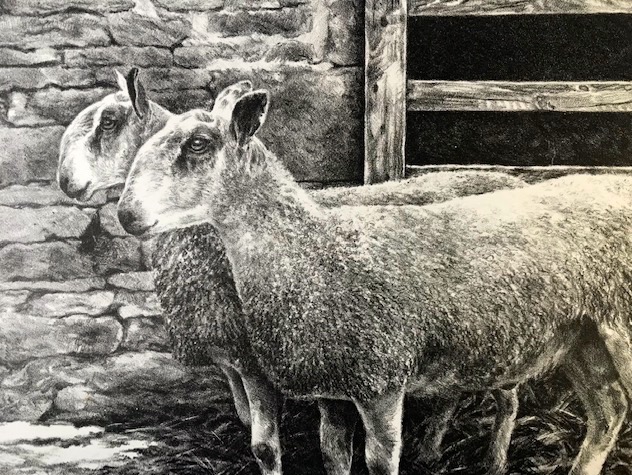

A traditional slate barn, dark and dominant, tops the hill we climb. By the hedge in a field we pass a new born lamb takes its first hesitant steps whilst the mother, trailing after birth, carries on grazing. We pass the curious ghostly remnant of a tree, fissured and blanched bark splayed like an animal hide.

We passed round a farm complex and cottages, walking downhill through pastures by a little stream and woods, where the National Trust’s estate husbandry was clear to see. Hedges thick set, high and well fenced, on a three year cutting regime (not annual) with a healthy mix of ash, hazel, blackthorn, hawthorn, holly etc. These hedges fulfill their primary function as stock boundaries while providing high conservation value as linear woodlands, a haven for a multitude of wildlife. It also acts as a retentive barrier against flooding and preserves the stream’s banks.

Large slabs of slate used as gateposts or hedges are traditional sights in a classic Lake District landscape. Delighted then to pass through a slate and wood style more turnstyle in appearance than step over style, complete with slide door for dogs.

Elsewhere there are giveaway signs that the oldest field gateposts are the ones with holes for sliding wooden crossbars that, in pre-mechanised times, were the norm in these parts.

The last stage of out ramble took us down a stony lane through mixed woodlands and pastureland to the Windermere shore line below the castle where we merged with lots of folk out for the day enjoying the Easter sun and the green open spaces on the long lake shore. The core purpose of the National Trust exemplified in opening to one and all what was once only available to the fortunate wealthy few.

The estate built vicarage is now a private home and a very smart one at that. Unlike the Victorian church of St Margaret just up the lane. Still owned by the Church of England and not the Trust it is now redundant, closed to the public on safety grounds. It stands forlorn and without purpose, though the cawing rooks nesting in the silent tower where bells no longer toll, call it home. I’m sure the Reverend Rawnsley would be saddened by the demise of his old seat but at least the spirit of the man lives on in his outstanding work to better the lot of humanity and making access to the countryside possible for countless generations to come. A legacy this delightful route through parkland and pasture bears witness to.

Footnote: Back in the late 1980’s I played Canon Rawnsley in an interactive site specific educational project for junior schools around Townend Farmhouse, Troutbeck. The Young National Trust Theatre Company I was part of at the time devised and performed these projects nationally – blending drama, music, roleplay and performance – for the National Trust in its properties nationally, sponsored by major blue chip companies and the Esmee Fairbairn Trust. Playing Beatrix Potter in this particular project was Roberta Kerr, my old friend and colleague from Theatre-in-Education days.