Oh! wail for the forest – the proud stately forest/No more its dark depths shall the hunter explore; /For the bright golden grain/ Shall wave free o’er the plain/ Oh! wail for the forest – its glories are o’re! (Catherine Parr Traill, Peterborough Gazetteer, 1845)

Some trees, like black walnut and western hemlock, dominate their spaces killing off competition from other arboreal species. Others, like the pines and conifers do it by height. It was the abundance of majestic white pine that first drew loggers here in force in the early 19th Century. Nearly all of the ancient big forest trees were felled then; initially to service Britain’s needs during the continental trade blockades of the Napoleonic wars and later more conveniently for the rapidly expanding American industrial market.

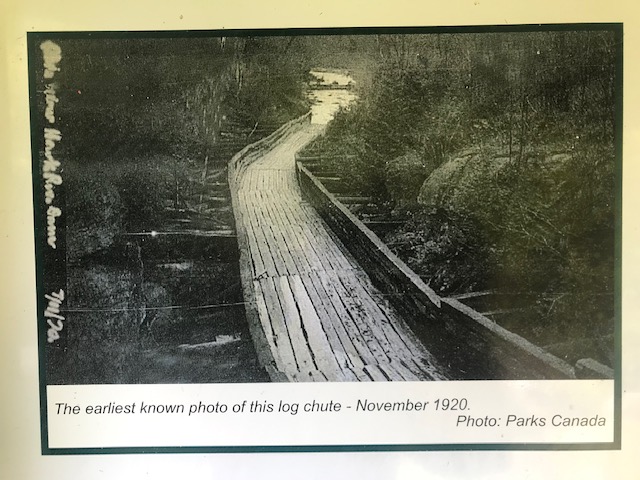

Our hosts hadn’t visited the heritage log chute before, and as we were keen to see it, a trip north towards the Algonquin National Park was eagerly anticipated. And we weren’t disappointed. The Kennisis river log chute, emerging from a dam on the Hawk lake, is the only one of its kind left, out of thousands that were once in action around the highlands. Built of secondary timber and used to carry logs over rough river landscapes to sawmills, log chutes were first developed in 1829 to circumnavigate falls in neighbouring Quebec.

Built by the logging companies, they were always attached to a dam on a lake where the logs were massed after felling, ready to be shot downstream on the Spring meltwaters. This one dates from the 1920’s and was restored as a national monument in the 1970’s.

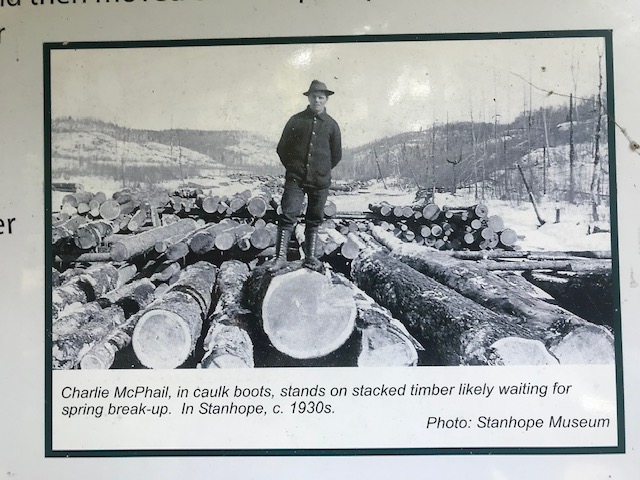

Great skill and daring were needed by those nimble footed workers afloat on the packed trunks wielding pikes resembling weapons of the medieval battlefields to deftly manoeuvre and feed the mass of felled timber into the mouth of the chute.

A vast swathe of hard metamorphic rocks stretches from the great lakes and the border with the US all the way north to the Arctic, the ‘Canadian Shield’ as it is known. Cuttings, where the highways pass, bear witness to the deep drilling needed to split the bedrock. This land is littered with erratics, blocks of igneous rock generated by the vast grinding glaciers of the ice age. The soils over this dense mass of impervious bedrock are thinly spread, only enriched by annual leaf fall and wood decay. It holds water in countless depressions, small and shallow as well as big and deep. Deciduous trees dominate this landscape – spruce, beech, oak, maple and birch among them, as well as pines and firs.

The dense mixed woodlands are home to many animals. Chipmunks dashing about the place in a number of spots on our trave. We were told that in the old days, before rubbish at the municipal centre was separated into various types for recycling, brown bears would be in residence openly rifling through the piles of waste for food, oblivious to man.

Hikers using the extensive network of designated all seasons trails are officially warned to ‘wear blaze orange in the fall as hunting is a part of the Highlands heritage….Remember you use the trails at your own risk”.