A weekend walk in the wider locality drew us to a favourite spot on the fell that defines our northern boundary of view. The only lay-by was full of cars. Shooters in the field. So we drove on down the other side, thinking where to now? Then I remembered a summer trek with a walking friend in a neighbouring valley, a place to which one day I swore to return…This must be the day.

Our part of Northumberland up to the time of Edward I’s imperial expansion over the border was relatively peaceful, which meant that most of the fortified houses and castles hereabouts were built by Scottish barons as their kings held sway here. Dally castle is a good example, overlooking a circling loop of the Chirdon burn. It sits impressively on the end of a ridge, part severed from it by a deep defensive ditch. Only the lower portion of its thick walls remain today, plus a generous scattering of dressed stone, including remains of columns and fish tail arrow slits.

Dally was originally constructed not as a castle but as a two storey ‘hall-house’ by David de Lindsay in the 1230’s. It was gifted him by Margaret, sister of King Alexander II of Scotland. Two centuries later, as times turned more violent and insecure in the age of the Border Reivers, that defensive hall was remodelled as a much more formidable three story ‘tower house’. Come the gradual return to political stability after the union of the crowns in the 17th Century Dally was eventually abandoned and dismantled. Its ready supply of dressed stone further depleted down the decades for re-builds of a water mill at its foot and additions to nearby estate buildings. Enough remains today to give a clear footprint and the site yields views over the alder lined course of the burn, in-bye fields and exposed fell sides flanking this now peaceful upland valley.

We followed our noses, having no map, driving on up the vale to find a parking place at the point it becomes a private access track. Continuing on foot we came to the forest edge where a surprising vista suddenly opened to view on our right. Roughside was a working farm until the 1950’s when the Forestry Commission took possession and evicted the last tenants. All its fields were then thickly planted with sitka spruce and the farmhouse and remaining outbuildings gradually disappeared from view as the trees grew up around them. Last year that whole stand of trees was clear felled and the isolated steading on its ridge came blinking back out of conifer confinement into the light.

Strange feeling it was to progress slowly uphill along the bridleway, crossed and crushed by the heavy plant used to clear the closely packed plantation. It was a mild day, clear sky, with no wind, so the air still bore the scent of resin from the stumps of pine and abundant brash. The farm’s former dry stone field walls breached in many places. Now, back in the sun, the accumulated seven decades of mosses that thickly line wall and ground will fall away under exposure to sun, wind and rain and the land take back some of its former wild character.

What saved the old farmstead becoming yet another forgotten ruin in the great post-war forestation was the action of the MBA in buying it from the Commission in 1989. The Mountain Bothy Association is a remarkable institution, formed and run by a dedicated band of volunteers. Founded 1965 in Galloway by local enthusiasts it’s a registered charity dedicated to maintaining otherwise abandoned buildings in the wildest, most remote parts of the UK as basic shelters for ramblers and backpackers.

The word bothy originally meant farm accommodation for itinerant labourers. Although the number of farm workers severely declined in the 20th century the number of leisure walkers increased so the functionality and adaptability of such places gave many a new purpose. Today over 100 such shelters are in the MBA’s care. Northumberland has 7 of the 11 bothies to be found in England, 3 of which are here in the Kielder Forest Park.

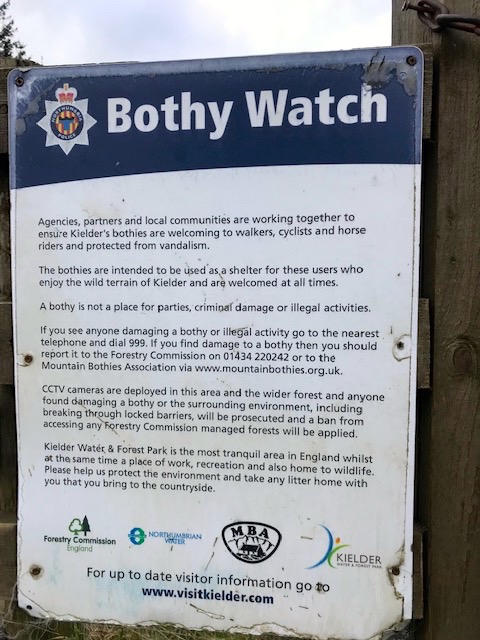

The Bothy Code is a common sense respect agenda. i.e. respect for other users, the surroundings and the building itself. In recent times selfish people turning up to party en masse with drink and drugs have caused problems, with additional issues of litter dumping and vandalism. A warning sign on the access track reminded us of that abuse.

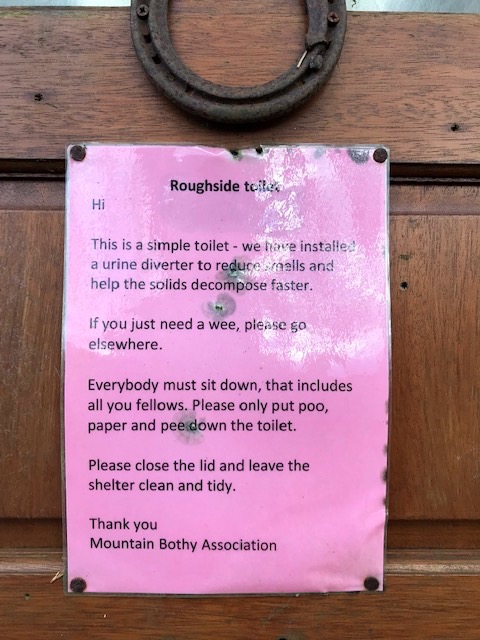

We set about exploring the various rooms in the old two storey building. All the basic necessities were in place, including saws to cut logs for the fire, carpet covered wood boxes to sleep on, a fresh spring water supply and an outside compostable toilet.

An MBA team visits to do structural maintenance and check all’s well. Our Goldilocks moment came in discovering one of the upstairs bedrooms to be occupied, although no one actually present, just all the walking and camping gear on two separate bed boxes and a roaring log fire in the grate!

We returned back down to the car by a slightly different route, skirting the forest edge where the rushing stream marked its boundary. Fascinated by the mature larch trees we passed, their bare branches swinging out over the wire fence, encrusted with lichen, cups of cones balanced elegantly on each bough.

The stream here, a headwater of the Chirdon burn, is narrow enough to stride over, and characteristically noisy, full of peaty brown water. Clearly it must carry force in spate, as the undercutting of the land at turning points clearly indicated.

We had parked near a handsome traditional stone built Georgian farmhouse, part of whose land fronting the burn had been transformed into a wild meadow garden, defined by circular grass paths and a large pond. The former farm’s single storey L shaped outbuildings had been converted into a pair of high spec fully equipped holiday lets, rebadged as cottages. Looking them up online back home we saw they were being let for an average £800 per week each. Made us smile to think we’d now seen, in one visit, both ends of the spectrum of accommodation on offer to visitors in our remote corner of England.