A week away in in late August, based in mid Wales, opened up opportunities for outings to new places. Family made arrangements for us to discover Mount Snowden (Y Eryri), the highest peak in England and Wales. The younger and more adventurous element booked their mandatory car parking slot on the mountain’s lower slopes and headed for the peak on foot while we senior members opted for the scenic route to the top by train, starting at the terminus down in Llanberis.

The Snowden Mountain Railway is unique in Britain in being the only one to use a rack and pinion system and was opened as a tourist attraction in 1896. Swiss made engines equipped with toothed cogwheels engage the rack to provide the necessary traction to climb inclines to the summit. A rebuilt modern terminus and visitor centre is tucked away under the peak and visitors have half an hour to enjoy the view before returning. We were really looking forward to the experience, whatever the weather. But our optimism was misplaced. The weather was very wet and windy. The station ticket office advised us that due to these adverse conditions our booked service would terminate three quarters up. We could either have our money back or proceed on those conditions. Having wound our way for nearly two hours on narrow roads over hill and dale to get here we stoically opted for the incomplete journey. Twenty minutes later saw us queuing up to board with the other remaining passengers, with steaming engine and carriage in sight, only to be told that this service was now cancelled. Alas, two thirds of ticket holders had opted for their money back. That left insufficient numbers of bodies on board to safely anchor the carriage, risking our being blown off the track by the high winds currently swirling round the mountainside!

We were refunded of course but were left inevitably disappointed and at a loose end. Also concerned for the rest of the family, with whom we couldn’t communicate as there was no phone signal. It turned out the hardy walkers got a good way there from their starting point and took in views of the lake below the cloud shrouded summit, before turning back after becoming drenched on an increasingly challenging track. We met up with them back at our accommodation near Machynlleth to exchange tales of the day over supper.

Our day out perked up when we realised what else the area offered. No-one can escape noticing that much of the mountain sides along the northern side of the valley are missing. A stark reminder of a relentless economic activity that has dominated and defined this area for at least two centuries – the mining and quarrying of slate. Turning into a large car park we came upon a barrack like old industrial complex, comprised, unsurprisingly, of slate roofs and walls. These are the Dinorwic quarry workshops, one of the imposing slate processing works that once made this corner of Wales the largest producer and exporter of slate in the world. At its late 19th century peak the industry employed 17,000 men and produced nearly a half million tons of slate a year.

The tall gatehouse of the dark castle like building looked even more fortress like and forbidding with waves of rain from remorseless grey clouds sweeping over it, but the welcome we received was warm and entry free. Dinorwic is now the National Slate Museum of Wales and has been invested in by its custodians the Welsh government since 1972 when it opened, three years after the quarry finally ended production. The site reveals itself as a succession of inter-connected workshops facing onto a large central courtyard, crisscrossed by rail lines. Opened in 1870, eight decades after commercial quarrying had begun on this site, it once employed some 3,000 men to repair, maintain, make and store all the machinery and equipment the vast operation, spread over 700 acres, required for its day to day operation. It even had its own dedicated hospital to deal with casualties on site.

My terraced house in Lancaster is one of the UK’s countless late Victorian homes and institutions roofed with Welsh slate. When I had the property reroofed in 2010, some 130 years after it had been built, 75% of the original Welsh slates were good enough to be reused. On our visit to the museum I discovered there was a regular boat journey from the main port for the slate quarries down at Portmadog to supply the Industrial conurbations of Lancashire, via Preston’s port on the Ribble estuary. This area of north Wales is where the slate for my humble home came from in the 1880’s, perhaps from this very mountainside!

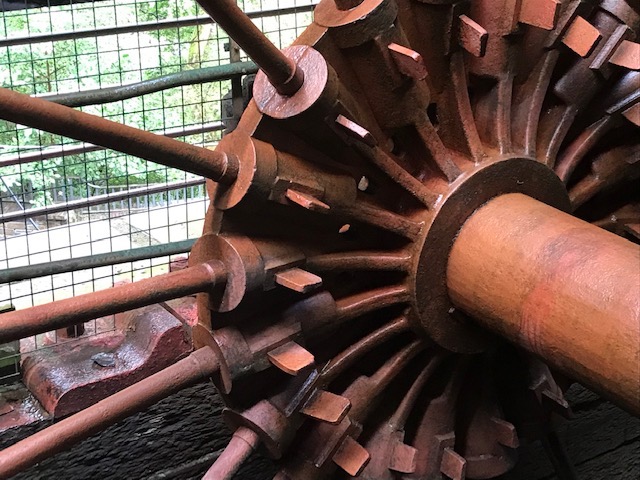

Highlights of our visit included getting up close to the works huge waterwheel, installed in 1870, driven by a stream running off Snowden’s slopes whose waters were piped across the valley. Measuring 50’ 5’ in diameter x 5’ 3” wide with a 12” axle this metal wheel is mainland Britain’s largest and sits confined in a narrow brick structure that makes closer examination a mildly claustrophobic experience.

Everyone loved the featured craftsman demonstration. A skilled former employee showed us assembled visitors how a slate is split with mallet and chisel. A deft act that drew a collective intake of breath in much the same way as a magician demonstrating a card trick might do. The wonder here being the sudden appearance of two perfect slates where there was only one before. We also learned that the traditional industry discarded a staggering 90% of excavation as waste, hence the distinctive landscape. Nowadays, much reduced manpower utilising modern mechanical means reprocess by-product as core material for the building, gardening, chemical and cosmetic industries. Quartz, chlorite, hematite and pyrite are amongst the minerals extracted.

Later, looking up from the courtyard at the scarred face of Elidir mountain towering immediately beyond I marvel at the pace of natural reforestation by native trees on former quarry terraces and into vast screes of slate waste. Oak, ash, hazel, willow and alder thrive and colonise, thanks to the wet climate and perilous slopes largely free from further human activity or grazing animals (feral goats excepted). An expanding nature reserve that’s good for wildlife too.

On entering one particular room off the courtyard, set up with tables and butty cans, the air resonated with interweaving conversations in Welsh. An effective audio visual touch. This was the mess room or Caban the men shared at break times. Pressing matters of the day, from religion to politics, sport and music were freely discussed here. At times the industry was convulsed with bitter disputes over pay and conditions. The great slate works were owned privately by gentry families that had been made immensely rich from the slate excavated on their lands while most of their many employees worked long hours in dangerous conditions for little money or job security.

A row of miners cottages, Fron Haul, originally situated near Blaenau Ffestiniog, has been rebuilt at the museum and refurbished to give visitors an idea of what domestic life was like for mining families at different periods, from the 1860s to the 1960’s. Years ago I’d been very impressed with another national museum of Wales – their flagship open air home of resettled buildings at St Fagans near Cardiff. This atmospheric recreation put me in mind of St Fagan’s fascinating row of post war pre-fabs, as furnished through succeeding decades.

We left the museum and crossed the tracks to take a ride on the former Padarn Railway that ferried finished slate to Y Felinheli near Caernarvon for export overseas. Closed in 1961 this initial section reopened as a heritage line, rechristened as the Llanberis Lake Railway. It runs from the village along one side of the lake, at the foot of the mountain. We enjoyed an hour’s leisurely ride, in tiny cabin carriages, five miles there and back, with the odd stop to take in the views and stretch our legs.

Caught a glimpse when trundling the rails of the quarry’s former inclines and terraces, a part of which has been recently restored. Powered by gravity, wagons full of slate travelled down the mountain, using their weight to pull empty wagons back up to the workface.

A totally different railway experience to our cancelled trip up Snowden but appreciated none the less for the modest delight it brought all aboard! The unexpected discovery of the slate museum in its country park though made our day. A place where nature, engineering and culture interact to offer curious visitors a surprisingly atmospheric and inclusive experience…whatever the weather!

A great write up, Steve. Love Sue x

LikeLike