The word paradise is derived from the ancient Persian – ‘A green place’. Paradise haunts gardens, and some gardens are paradises….Christopher Lloyd’s Great Dixter (for one). It’s shaggy. If a garden isn’t shaggy, forget it. (Derek Jarman)

We are always on the borderline of what it’s most sensible to attempt. Such gardening may be silly, but on the other hand, it can be the most exciting. (Christopher Lloyd)

First it was Covid then the uncertainty caused by rolling rail strikes but third time around we finally made it to Rye in East Sussex this month. The trip was spurred by a wedding present of free entry to one of the UK’s most famous and best loved gardens, Great Dixter.

We arrived on the south coast from Northumberland by rail and the next day caught the regular service bus to the pretty village of Northiam. The subtle range of old red brick and white painted clapperboard houses put Kim in mind of Quebec’s eastern townships from where her mother’s family hailed and where she spent many a happy summer vacation.

Our way took us under some of the magnificent great oaks this corner of England is famous for. Trees that once provided the timber to build naval and merchant ships as well as local farms and manors, including the one we were about to discover.

Great Dixter was the family home of the famous gardener and gardening writer Christopher Lloyd OBE (1921-2006). His father Nathaniel was a retired wealthy businessman with a love of the arts and craft movement. In 1910 he bought the C15th farmhouse with its oak framed great hall (the largest of its kind in England) and commissioned Sir Edwin Lutyens to design a complimentary wing in brick and tile. At the same time a derelict Tudor timber house at nearby Beneden was bought for £75, dismantled and re-erected to form a further part of the enlarged home.

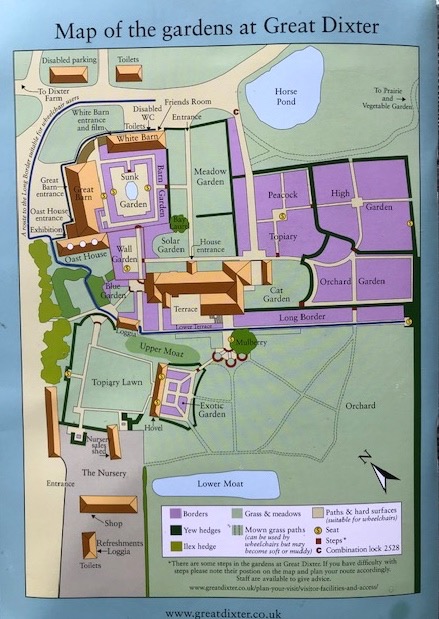

The garden plan was initially sketched out by Lutyens and implemented to the designs of George Thorold who, working closely with the Lloyds, converted yards, hedges and fields into a series of interlinked garden rooms bound by the existing great barn, stables and oast house. It was Nathaniel’s wife Daisy (1881-1972) who oversaw the planting and evolved its development under the influence of leading practitioners like William Robinson and Gertrude Jekyll. Christopher (Christo) was the Lloyd’s sixth and youngest child and he spent an idyllic childhood immersed in the bucolic world his loving parents had created for the family at Great Dixter. His mother Daisy supported and encouraged him in his stewardship of the gardens up to her death in 1972.

After leaving for university, then war service and further study in ornamental horticulture Christopher finally returned home in 1954 and started a nursery and began experimenting in the gardens. In so doing he pioneered the dense mixed flower border using colour, foliage and structure, in contrast to the purely herbaceous formal border that was then the norm.

He loved using seed raised annuals, prizing them for their vibrancy and vigour, and would eventually grub up the rose garden to replace it with an exotic one, another influential step.

Christopher Lloyd was as an eminently readable writer and his horticultural leadership role at Great Dixter is carried on today by Fergus Garrett, head gardener since 1993, under the auspices of a charitable trust. The two men had become firm friends, generating a creative synergy, ensuring it continues to be a place of experimentation and change.

The nursery, cafe and shop are clearly thriving businesses. Young gardeners from around the world study here and thousands visit every year to be inspired or challenged by what they find. Us included.

I confess to that floral bathing in the tall yew topiary bound Orchard, High and Peacock Gardens felt more combative than contemplative for my taste. After a while it all began to loose distinctiveness and become simply a glorious abstract blur. A sense of being on the outside as opposed to being drawn in was probably accentuated by the exuberance of growth and sheer numbers of fellow visitors.

Being a lover of garden ponds I appreciated getting a view of the farm’s former horse pond but would have liked to got nearer to it than we were able to from the approach road.

What I did love though was the escape offered in meandering along mown paths through the peripheral orchid rich meadows. Fine views too of the house afloat on its surrounding sea of trees shrubs, topiary and flowers.

Found myself captivated by the bold contrasts of stone paths, low wooden outbuildings, sculptural forms and slim beds of swirling foxgloves that define the topiary lawn quadrant between the great barn and plant nursery. Perhaps the sense of potential outdoor theatre setting it evoked was the key to that feeling.

Great Dixter has a stated mission to further unlock the ecological potential of its ornamental gardens. A 2017 audit identified 2000 species within the estate. That tally included 270 types of moth, 148 species of spider and the rare Mining Bee.

Resting from our wanderings in the heat we sat on a shaded bench, watching the birds flying backwards and forwards from their nests under the eaves of the grand house. That and the simple pleasure of following meadow brown or gatekeeper butterflies weaving their erratic courses through the meadow flowers in this, one of the most quintessential of English garden sanctuaries.

Caveats notwithstanding I was very glad we’d visited Great Dixter to understand its unfolding history and inspirational legacy. One that continues, as all great gardens do, to find renewed meaning in our own time.