The big show to attract many visitors to Mull in the 21st century has highlighted the profiles of its three star turns; otters, white tailed eagles and golden eagles. The RSPB reckon that some 160 jobs on the island are dependent on bird watching alone. The glorious triumvirate were not the main driver for our visit but the delightful encounters we had with them provided some truly unforgettable moments.

It takes constant low level attention to drive properly along Mull’s single lane roads so it repays letting someone else take the wheel. When that companion has intimate local knowledge of both territory and creatures that inhabit it then it’s well worth the relatively modest cost involved to secure their services. Andrew Tomison is one of those people. The former salmon fisheries scientist also hosted five other folk on our day out and we made for a convivial crew, taking turns to sit in different seats in his minibus to vary the views and Q&A’s. (https://wildlifeonmull.co.uk/) Pulling in to passing places or overtaking where required we cruised over mountain passes, through woods and forests and around sea lochs in the quest to view those leading players in action.

One of my favourite books growing up was Tarka the Otter by Henry Williamson. Charles Tunnicliffe’s brilliantly rendered illustrations perfectly complemented the drama of the dog otter’s ‘Joyful water life and death in the county of the two rivers’. I’d viewed sea otters at Monterey on a visit to California two decades ago but apart from animals in zoos or wildlife parks I had never seen a Eurasion Otter (Lutra lutra) in the wild, until now.

Mull has 300 miles of coastline and both inland water and sheltered sea lochs, making it the perfect environment to sustain a healthy population of otters. Much of the island’s network of narrow roads hugs the coastline, which is rich in kelp embedded on the ancient rock formations, the perfect intertidal hunting and resting environment for these extraordinary mammals as they move from inland freshwater hunting grounds to favoured seaside haunts. Thanks to their helpful human allies in the Mull Otter Group (www.mullottergroup.co.uk) motorists are reminded to look out for them crossing.

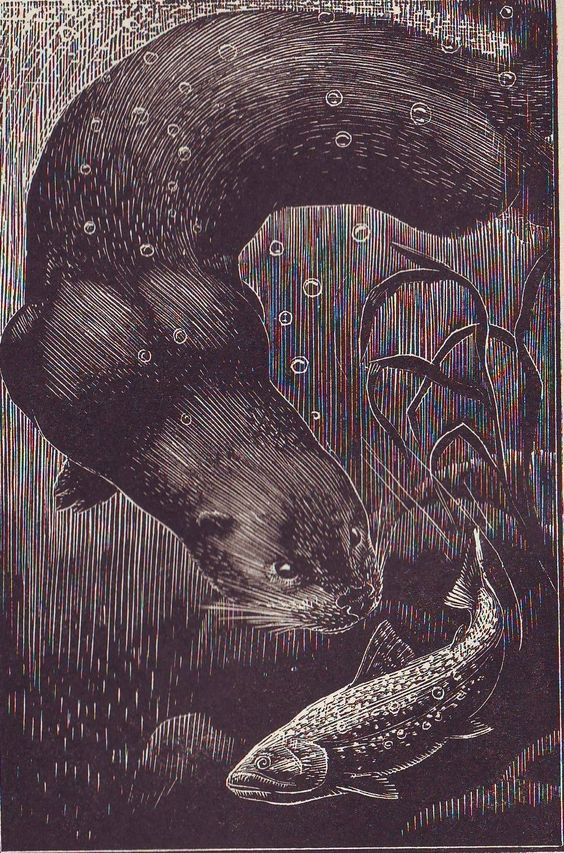

We saw the spotters before we saw the otters. Some dozen or so folk, standing stock still, hid behind bushes or sat on rocks, binoculars or long lensed cameras poised, focused on the shoreline some eighty yards distant. The minibus parked and we decanted quietly to swell the numbers. The phone camera cannot do justice to what I saw over the following half hour so here’s an image from a professional that will give a feel of it.

Cubs (usually two in number) stay with their mother for up to two years, learning all they need to know to survive. It was such a family threesome we were thrilled and privileged to see in action here. I think one of the reasons otters appeal so much to us is that they make killing look like fun. Whether in full acrobatic pursuit of fish and crabs underwater or rummaging through layers of wrack on shore to extract shellfish and other marine life hiding out there. The constant interactive playful nature of otters in this context is truly mesmerising. As indeed were the stiller moments we witnessed; eating, grooming, playing.

What a perfect set of evolutionary characteristics. Their webbed feet each have five clawed toes for gripping slippery prey securely. A predator’s set of 36 teeth within strong jaws, combining backward curved canines and sharp molars. Two layers of fur. A very fine dense inner layer within a waterproof guard layer of coarser hairs, constantly groomed to retain its water repellent and warming properties. The otter manages in that process of grooming to trap a thin layer of insulating air between each layer and can self regulate body temperature. We could see too that the family group in water had sleeked coats, which when back on land became instantly spikey, a sign of their good health.

Where Eagles dare. A safe distance from man, that’s for sure. After centuries of being driven to extinction due to the shooting interests of the huge sporting estates across the highland and islands these magnificent birds are now firmly back in place as the island’s apex predators. The UK’s largest bird of prey, with a wingspan up to two metres, the white tailed or sea eagle can be found in greater numbers here than anywhere else in Britain. The outlawing of harmful agri-chemicals like DTT, tough new protective legislation and scientific re-introduction programmes from the 1980’s onwards have enabled both species to gradually reclaim their empires of air land and sea here in the Western Isles.

Andrew, ever the genial guide, was good in getting us to understand the differences between the species as we set up to view their various nesting sites from a safe distance with the aid of his binoculars and tripod mounted telescopes. The whites have broad wings and fanned tails compared to the golden’s narrower wings and longer tails. The hunting characteristics and styles he described were fascinating too. The sea eagle’s precise glide, grab and lift of fish to golden eagles, from their eyries on inland cliffs, who have learnt to hunt the red deer that are so numerous hereabouts. Working in tandem they fly low over the terrified animals in order to stampede them over the cliff. They can then feast on the broken bodies below at leisure. Carrion for both species is an important supplement to live catch as their daily average food requirement is around 250 grams. Regulations allow farmers to be compensated by the government for any proven predation of spring lambs.

At one inland site between mountains we viewed a white tailed eagle well hidden in an isolated stand of commercial conifer plantation on a precipitous hillside. Its fearsome yellow hooked beak was the principle feature to catch the viewers eye at a distance. The rest of the dense forest had been clear felled but, with the discovery of the nest, all mechanical forestry activity within one kilometre of the eyrie had, by law, to cease immediately until any chicks had fledged. Quite something to see the needs of nature aligned with those of tourism, placed equally in the scales with economic and cultural interests.