Where we were staying in Forest Hill was one of 2,000 built in a joint operation between the Dulwich estate and the volume house builder Wates between 1957 and 1969. The high spec architectural design and green setting applied to all the homes constructed at this time around the 1,500 acre estate. My cousin’s home was one of many linked terraces built on the site of five large Victorian villas. Subsequently many of the trees surrounding the enclave are of some vintage. Copper beeches, pines, sycamores and ash make for a dense green curtain at the end of back gardens, blocking out traffic noise and pollution but depriving them of full sunlight and harbouring the usual urban garden menaces, from feral pigeons to grey squirrels. Something I’d not clocked before were the bags at the bottom of recently planted trees. Closer examination revealed them to be self regulating reservoirs supplying water to sustain them at this crucial stage.

Dulwich was once a landscape of farms, woodland and commons, part of the Great North Wood, the property of the Bermondsey priory in the middle ages. The name for the settlement, dating back to Saxon times, means ‘Dill Farm’. The Dulwich Estate traces its history back to 1605 when the great actor and wealthy businessman Edward Alleyn (1566-1626) bought the manor for £5,000 from its post Reformation owner, going on on to found and oversee the charitable trust that bears his name, endowing a school, almshouses and chapel. Alleyn and his father-in-law and business partner Philip Henslowe were the greatest entertainment impresario of the age running both the Rose Theatre at Bankside and the Fortune on Finsbury Fields. Their individual account books provide an invaluable insight into the workings of Elizabethan and Jacobean theatre. Alleyn was also ‘Master of the king’s games of bears, bulls and dogs’ while as an actor he performed the title roles in the premieres of Marlowe’s plays Tamburlaine the Great, Doctor Faustus & The Jew of Malta.

The alms houses and chapel (where Alleyn is buried) still stand and across the road from them are the grand gates giving entrance to another part of the estate inheritance – Dulwich Park. Originally five fields of farmed meadowland, it became a public park in 1890. I loved seeing the lines of ancient oaks – original boundary features of vanished hedges and lanes – standing broad and elegant in the Victorian setting of walkways and shelters. Later we watched the ever pushy pigeons hustling for food where folk were feeding the goldeneye ducks, moorhens and coots on the boardwalk through the central lake by the densely wooded island retreat where the birds can nest.

Another delightful corner of Dulwich village is the new orchard and wildflower meadow on the former playground of the old grammar school. It was established on its three quarters of an acre site in 2019 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Alleyn’s charitable foundation and is very much part of the re-greening agenda that the estate promotes across its operation. Other pocket orchards are planned in years to come. The estate also lets out some 40 acres of allotments as well as a dozen playing fields for public use.

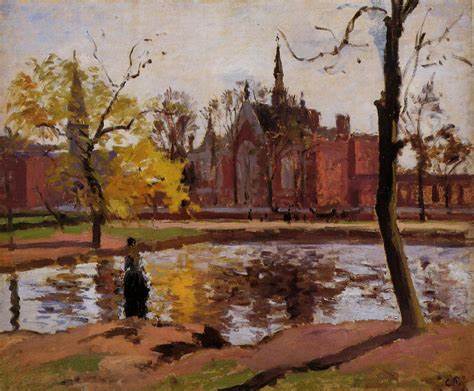

I was curious to note as we drove by it, the former millpond in front of Dulwich College, now totally surrounded by trees and shrubs and whose surface is completely carpeted with pond weed. It looked very different when painted by Camille Pissarro in 1871. In an age where the horse was the base unit of transport numerous roadside places for them to drink would have been commonplace. As every pond wants to commit suicide when left to its own devices (i.e. it silts up and fills) I wondered whether letting re-wilding run its course in our time might be counterproductive to maintaining a healthy water ecosystem. I also suspect that any public body clearing vegetation of any kind automatically risks protest and disapproval by the public. Even if that were not the case, easier public access would automatically increase the likelihood of someone drowning and all that implies for insurance, signage and prevention. Who knows, fifty years hence it might well be a mill and pond again, generating clean renewable energy!