Living as we do in England’s least populated county it’s always something special to get on the train and immerse ourselves in the cut and thrust of London’s city life. Our most recent visit was last weekend, to catch up with family living there, which fell into different phases for this blog. Here’s the first post, about our walks around Forest Hill.

Once upon a time a large chunk of what is now south London, stretching from Croydon to Camberwell, was known as the Great North Wood. Its extent in medieval times was some 20 square miles (52 sq. km), consisting of ancient woods, wooded commons and villages. At its productive peak (up to the early C 19th) these Surrey hills were at the centre of a thriving economy which provided charcoal to fuel the capital’s ovens and forges, timber for its houses and Royal shipyards at Deptford and oak bark for the extensive tanning industry centred in Bermondsey. The Industrial revolution replaced charcoal with coal and with the capital’s population boom, enclosure acts and the coming of the railways the Great North Wood began to fragment and disappear, giving way to a sprawl of suburban villas, roads and shops.

The memory of places live on in names like Norwood (‘north wood’) Forest Hill, and Penge (‘edge of wood’). What’s left – in the form of woods, commons, gardens and parks – is now better protected and looked after than ever before; an invaluable recreational facility and interconnected series of nature reserves.

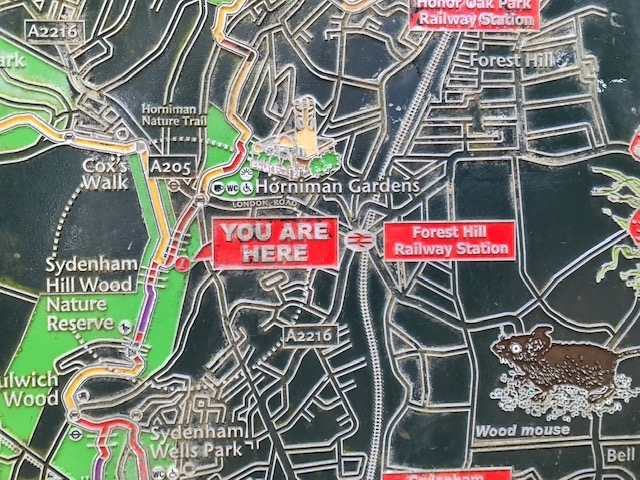

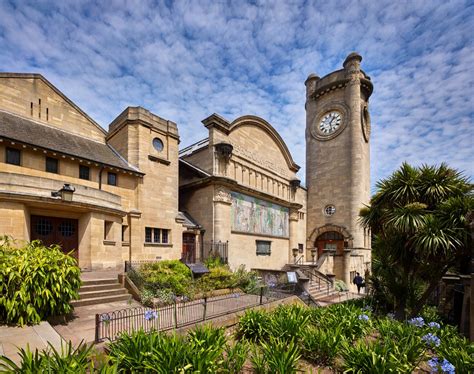

In Forest Hill we went walk about guided by my cousin, who has lived here for the last 40 years. We strolled through a patchwork of restored meadows, under old specimen trees and by high hawthorn field hedges, all combining to screen and subdue the sound of heavy traffic on the South Circular Road, AKA the A205, streaming by outside the building and grounds that dominate the hill top ridge here – the Horniman Museum and Gardens.

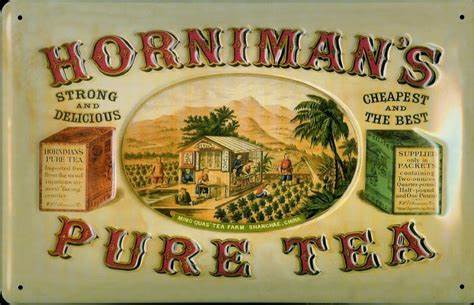

One of the newly enriched professionals who made healthy heights of Forest Hill their new home in the late Victorian era was the Quaker Tea Merchant Frederick Horniman.

An extensive world traveller, attending to the expanding family business (est.1826), he had amassed a huge collection of natural history, cultural artefacts and musical instruments. They initially went on display in the family home but the collection eventually got too big to accommodate so the indefatigable philanthropist commissioned the daringly modern arts & crafts style institution to house it that bears his name. The building opened free of charge to the public in 1901. The 15 acres of gardens and grounds opened earlier, in 1895, the same year that Frederick became a Liberal MP. Lots of additions and changes since to both house and grounds to reflect society’s expectations and last year the Horniman won the prestigious Arts Fund museum of the year award.

‘Second Hand Sunday’ is an outdoor market held in the grounds and gardens, which also boasts new hedging by the main road, medicinal garden, butterfly house, dry gardens, bandstand etc. After sampling what was on offer and enjoying the impressive view over the massed high rise towers of central London we ambled down the steep park slopes, past dog walkers, children playing and picnickers to the tree lined edge and nature reserve on its northern boundary.

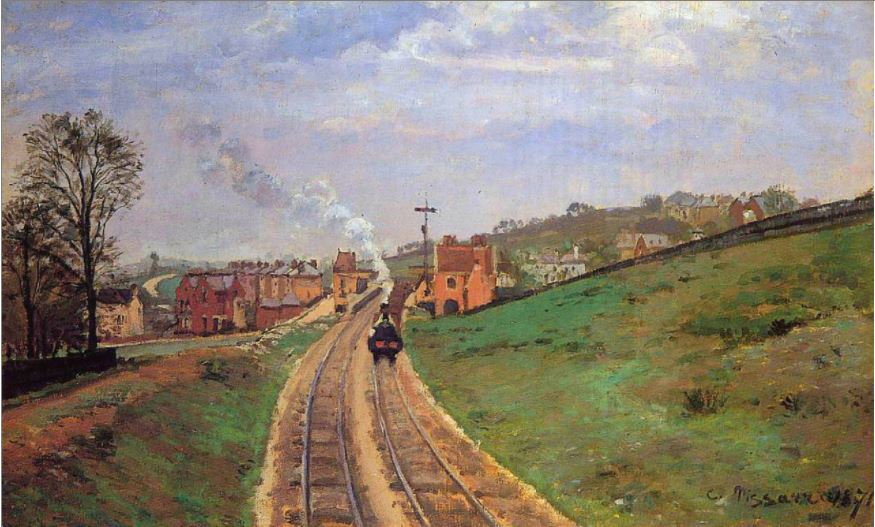

The Horniman nature trail is the oldest in London and was originally a section of the Crystal Palace and South London Railway, AKA ‘The High Line’, which opened in 1865 and closed in 1954. After closure this half a mile stretch was left unmanaged and reverted to woodland and scrub. Dividing Horniman parkland from terraced housing, it has been managed as a nature reserve since 1972 and the linear site features a pond, log piles and wild flower meadow. Visitors can discover, at different seasons, gatekeeper butterflies, common toadflax, jays and many members of the tit family.

The painting of Lordship Lane station by Camille Pissarro gives a sense of the railway back in 1871. The great French impressionist painter lived nearby at Crystal Palace then with his family, in self imposed exile, during the Franco Prussian War.

The High Line, further on its course to the tunnel that emerged at Crystal Palace, split the remaining remnants of the Great North Wood even more. Now that the old line is a public footpath, Sydenham Hill and Dulwich woods have been re-united as one entity (and largest extant section of the GNW). It’s custodian is the London Wildlife Trust, which has combined forces with other public bodies and charities to take advantage of government grants and allowances to conserve nature and promote public engagement while also restoring and creating new habitats to make a living landscape relevant to the needs of both people and wildlife. Very impressive it is too and shows what can be done when the collective will is there.

We discovered the unobtrusive entrance to Cox’s Walk, an unpaved track parallel to the old railway path, dating from the early C18th, and marvelled at the newly emerged greenness of the dappled canopy above and dense undisturbed undergrowth below. Tall metal railings painted black either side of the steep narrow path have clearly played a part in that. Designed no doubt to guard against illegal tipping and ingress from people and dogs, thus shielding the site for natural renewal.

We left Cox’s Walk at a junction to follow a desire path that emerged out of the wood, onto open lawns round blocks of council flats, to cross a busy road and into the quiet residential close where we were staying.

Footnote: Frederick & Rebekah Horniman’s oldest child Annie (1860-1937) was a leading figure in the development of modern British Theatre. One of the first women to graduate from the Slade School of Art, she used her considerable inheritance to work with WB Yeats and GB Shaw to co-found and produce for the Abbey Theatre Dublin between 1904 – 1910. She then funded the building and development of The Gaiety in Manchester, the first theatre to be run as a repertory. That Frank Matcham designed building became the base for premiering realistic dramas of working class life by locally based playwrights like Harold Brighouse & Stanley Houghton. The Abbey went on to become Ireland’s National Theatre while the Gaiety was demolished in 1959 to make way for an office block.