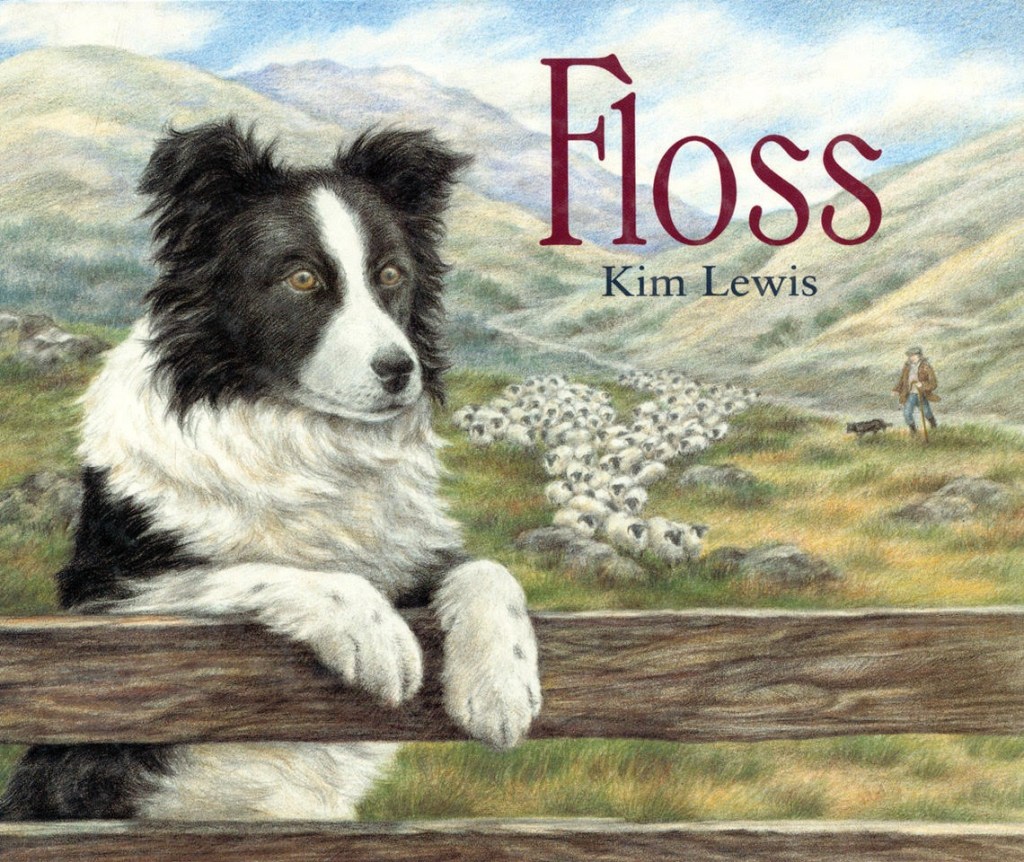

‘Somewhere in Northumberland is the working sheep farm where Kim Lewis writes and illustrates the books for very young children that have been shared by countless parents and boys and girls around the world. She draws what she sees around her and provides us with an intimate portrait of farm life in the remote rural north-east . . . The natural rhythm of the countryside: the routine of each day, the passing of the seasons, the birth of young animals and their growth to maturity, are all part of the cycle of stories that reflect different stages in the development of very young children . . . . . Kim’s stories and her pictures are one of the best attempts you are ever likely to find at capturing both the magical kingdoms of early childhood and some special places in the Northumberland countryside that are still out there to be rediscovered.’ From: Journey to the Hidden Kingdoms by James H Mackenzie; A Guide to the Children’s Books of Newcastle, North Tyneside and Northumberland

Our most recent walk was a new one for friends staying with us last weekend but not for Kim. Anyone familiar with the children’s picture books she wrote and illustrated for twenty years when farming here in Northumberland with her late husband Flea (Filippo) will have a sense of the upland landscape in which those wonderful stories are rooted. Kim rarely has cause to return to her former home these days so our three mile varied perambulation over fields and fell and by woodlands and along the river was also an emotional immersion in her past.

Weaving through a housing estate on the edge of the big village which is the dale’s main settlement, well supplied with local shops and facilities, we gently ascended a metalled track to reach an old farmhouse and outbuildings. Looking back the horizon hugging wind farm looked closer than it is, revolving arms reflecting low afternoon sun against a dark sky.

A steep ascent followed as we crossed a stile onto the land that Kim and Flea managed and bought up their two children. A thousand acres, mostly rough grazing on open fellside, supporting a herd of suckler cows and 600 Scottish Blackface sheep. The large farmer and stock breeder they worked for in turn rented this farm from the upper valley’s main landowning family in residence at the big house across the river. That family were the principal Reiver clan during the feudal era here in the Borderlands where the Kings of Scotland and England were rulers in name only and localised power lay in the hands of the warlords and their various shifting affinities, bound by blood ties or tenancy, securing life and livestock in fortified stone buildings known as bastles or peles.

In the wake of near constant rain the ground was soaked and had been widely poached into thick mud by the feet of hundreds of sheep crammed around ring feeders and low loaders where bales of hay had been dropped. A large mixed flock of Blackies and Swales watched our progress with cautious curiosity as we passed through the old quarry with its clitter of abandoned rock, then along the deeply rutted puddled track where generations of carts, tractors and quads had passed. Kim set a number of scenes on this exposed moorland with sheep and border collies in action mode. Like this snow scene with the escaped puppy in ‘Just Like Floss.’

The view from the top of the escarpment was a gorgeous one, albeit part blinded by the lowering sun. We paused by a local landmark, which also features in Kim’s illustrations. The weather worn ‘lone pine’ now has the close company of another, planted by Flea to keep continuity, as the original started to die back.

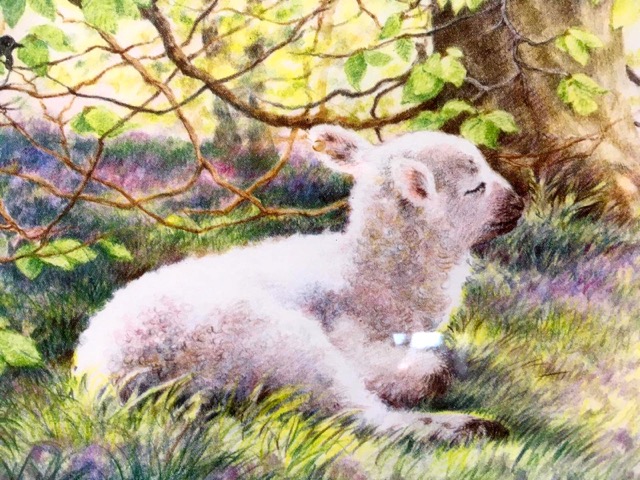

We descended to pick up a small stream, passing a couple of sheep carcasses picked clean by predators, then through a gate into a field which contains an old oak wood. This covers the site of a Romano-British settlement, at least 1800 years old, consisting of at least four round huts and subsidiary stock pens within an outer ditch and bank. These typical features remain as faintly delineated earthworks and were the subject of a university excavation in 1958 that established the steading’s lay out and structure and lead to its eventual listing in 1973, over a decade before Flea and Kim took on the farm.

The wood in being grazed by stock is unable to fully regenerate. The remaining woodland on the other side of the fence though is ungrazed and can grow naturally. During his tenancy Flea had that part of the woodland fenced off and even transplanted saplings by hand to help the natural process along.

Immediately below the trees lies the trackbed of the former Border Railway, following the valley contour, cutting clean and deep across our downward path. Here a fine old footbridge has been restored and is maintained by National Park volunteer rangers, allowing walkers to cross in style from bank to bank.

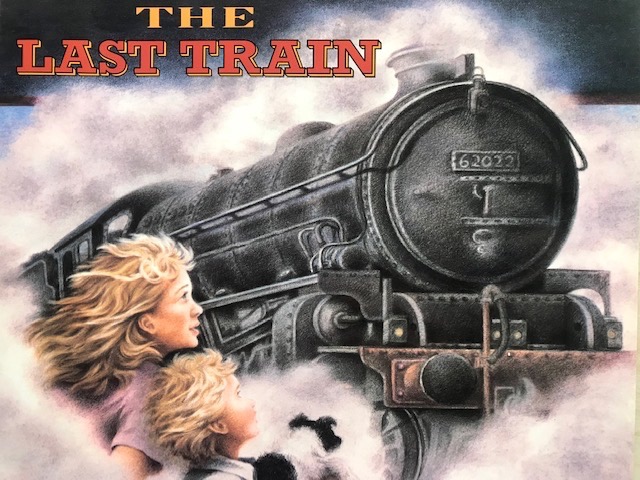

Kim set one of her most creatively atmospheric adventures (a personal favourite of mine) in a linesman’s hut just below their farmhouse, entitled ‘The Last Train’ The National Park also restored the hut out of respect for the line & the story.

Reaching the valley road we turned back towards the village and after a few hundred yards left to follow the river along its bank aside the farm’s flat meadow hay field and banks of copses back to where we started.

We enjoyed a view across the water through an avenue of limes of the grey stone fronted Palladian mansion that gives a panoramic view of an extensive landscape in its charge.

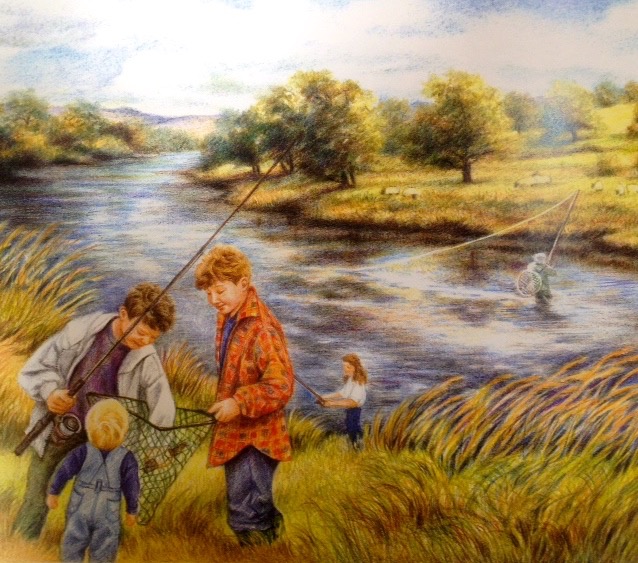

A bend in the wide river revealed a local bathing and swimming stretch, a scene captured in illustrations for ‘One Summer’s Day’.

Taking advantage of a fine January day this was a revealing walk in so many ways, and one to savour, made the richer through Kim’s intimate connection with the land and those who work it, which in turn gave life to stories and imagery shared with generations of appreciative readers in this country and abroad.