‘There is one, even Jesus Christ, who can speak to your condition’ George Fox

In my former day job, tour guiding at Lancaster Castle, I’d often explain the place’s connection with George Fox, the C17th religious revolutionary who faced trail at the assizes and was subsequently gaoled here for being ‘troublesome to the peace of the nation’. The firebrand preacher and his followers were viewed as underminers of the class system who thee’d and thou’d everyone regardless of rank; treated men and women as societal equals; refused to recognise the authority of the established church and wouldn’t swear oaths or bear arms. Self styled ‘children of the light,’ they were seen as extreme non-conformists who suffered persecution and imprisonment until religious toleration from the late 1680’s eased their condition and helped merge them into mainstream society.

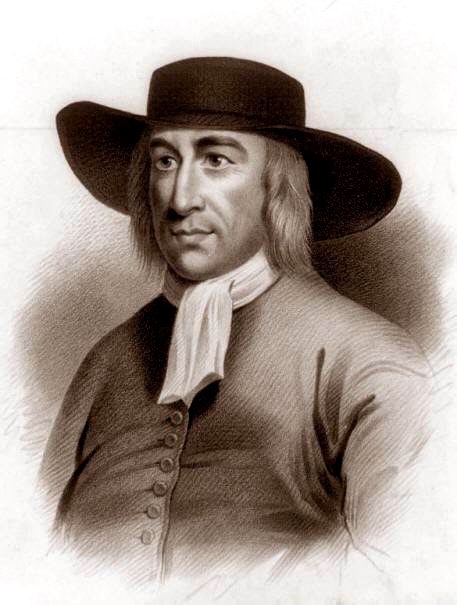

The movement’s charismatic founder George Fox (1624-1691) was a self-educated itinerant preacher with extraordinary self-confidence and resilience. Inspired by God given inner light or ‘openings’ the charismatic young man must have found his apprenticeship as a cobbler useful in effecting running repairs after travelling on foot over for many miles on terrible roads, staying at safe houses hosted by followers. Despite many setbacks the weaver’s son from Leicestershire effectively founded and led until his death a highly organised grass roots movement that would become known as the Religious Society of Friends. The contemporary name of ‘Quakers’ derived from the elated physical state of its most devoted followers at meetings. Forbidden by law to establish themselves or preach in towns Fox and his associates concentrated operations in the remoter parts of the north of England where it was more difficult for civil or church officials to monitor or suppress them. Hence the great outdoor gatherings on Pendle hill in Lancashire and Firbank Fell in Westmorland in the summer of 1652, during the Republican Commonwealth, which would mark the body’s establishment.

The young Fox abhorred the licentiousness, earthly vanity and wanton entertainment of performers he witnessed in his youth. With a wry smile I suggested to Kim we visit Firbank Fell on the way back home from a recent day trip to Kirby Lonsdale. The Old Smithy in that attractive Lunesdale town is a well preserved listed building that dates from Fox’s time. Odd as it may seem, this is where we travel two hours to in order have our respective hair expertly cut every three months or so by an old associate from Lancaster days Alex Toubas, whose salon now occupies this wonderful barn like space. En route home we’ll often go for a country walk, drop by a favourite nursery, garden or gallery, discover a new historic site or call in on old friends.

I wanted to introduce Kim to an unusual and little known heritage site, taking advantage of the good weather, before predicted snow and ice arrived. ‘Fox’s Pulpit’ on Firbank Fell where he preached to a huge crowd is still a remote spot, accessed by an unmarked lane off the Sedbergh to Kendal road that climbs and twists its way up past a farming hamlet to the fell summit.

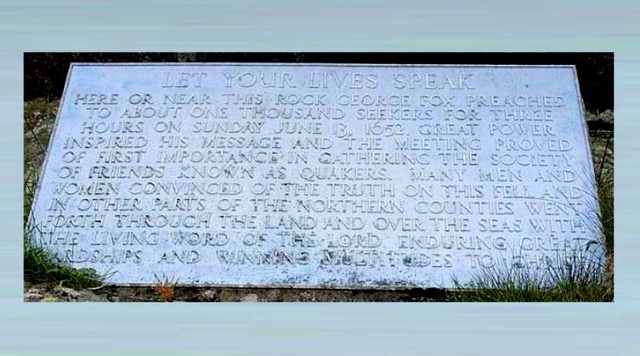

There’s little room on arrival to park on a laneside hemmed in by drystone walls. The small field here reveals itself as an abandoned graveyard, with one lonely gravestone the only obvious clue to its origin. The little chapel that once stood here was demolished following a violent storm in the winter of 1839-40 and was rebuilt on the other side of the fell. The rock from which Fox addressed the mass of ‘seekers after truth’ on that summer’s day is an impressive natural feature, now marked with a memorial tablet, erected to mark the tercentenary in 1952.

Fox later described the event in his ‘Journal’. While others were gone to dinner, I went to a brook, got a little water, and then came and sat down on the top of a rock hard by the chapel. In the afternoon the people gathered about me, with several of their preachers. It was judged there were above a thousand people; to whom I declared God’s everlasting truth and Word of life freely and largely for about the space of three hours.‘

We enjoyed a clear sky view over the lush wide valley southwards. In the other direction stretched a landscape of further slopes and hill tops with no discernible habitation in sight. Our ears became attuned to today’s multitude – not people, just sheep and the faint steady hum of unseen far away vehicles. The subsequent lonely drive from here to join the motorway down at Tebay is a fabulous scenic drive to match any other, whatever the season. A backdrop of the distinctive Howgills to the west and the eastern extremities of the Lake District hills the other side, with west coast railway, motorway and river Lune overlapping and threading through the gorge alongside us, all on different levels.

No time today to introduce Kim to another highlight of ‘Quaker Country’ in the valley below Sedbergh, where the country’s second oldest Quaker meeting house (1675) is found tucked away by a farm at Brigflatts. Years ago I gave a reading in that beautiful peaceful spot, partnering the recorded voice of the late Basil Bunting, co-reading his celebrated poem Brigflatts, a work inspired by his time living here as young man. Our live event was part of the town’s annual arts festival, the brainchild of locally based sound sculptor and graphic designer Andy Chapple, who mixed and played the live and recorded soundtrack on the day.